This is my dissertation written for the mastercourse MA: Photography and Urban Cultures, at the department of Sociology at Goldsmiths, University of London (2015).

How does the cinematic influence our perception of time and space in relation to photography and the city?

Abstract

This dissertation provides an insight into the intersection of photography and film. It investigates the notion of the ‘cinematic’ and its influence on time and space in relation to urban photography. The ubiquity of the moving image has to be taken into account while its language determines the toolbox of many photographers including the author. Photography is a time-based medium like film. To address this issue this text will apply film theory to photography in order to elucidate the cinematic in urban theory. The cinematic effect and affect will be analysed with examples of work of both photographers and filmmakers. Finally, images from the author’s project are placed in the ‘stillness-movement spectrum’.

Introduction

This paper is an exploration of the influence of cinema on photography. I will (re) define the key concepts of these fields and focus on the art forms that manifest at its intersection. Secondly I will examine the life-long relationship of cinema with the metropolis. Through this study I will try to get closer to the understanding of the ‘cinematic’ and suggest a news meanings for what it might involve.

The starting point of this dissertation comes from personal experience in the field of photography and film. My photographs are often described as ‘cinematic’, but no one has ever been able to give me an appropriate description of this meaning. In the art scene it has the negative connotation of being populist and sensational. In the editorial field it has a positive connotation for its atmospheric and suggestive character.

Inspired by Chris Marker’s La Jetée and Fritz Lang’s Metropolis, I started experimenting with film in the photography department of the Royal Academy of Fine Art in the The Hague, the Netherlands. Fifteen years ago I seemed to be the only one in the course interested in film. In fact, when I wanted to include moving images in my graduation project I was discouraged to do so, and rather stick with the still image. Back then the paradigm was: first master your own medium before exploring others, while I argued that one can only understand ones own discipline by investigating the borders. Nowadays film has become a mandatory field of study in most photography courses.

Because the technique of film has become available and affordable for everyone, we are now surrounded by moving images. Photojournalists are assigned to produce video and audio alongside their photographic essays. It is estimated that in 2016 video will represent 55% of the all internet usage (Corbis, 2015). The future of photography is in its interaction with other media. Many image makers started to explore the threshold between the two. I worked extensively in the film industry as a photographer producing film stills, portraits and posters. From these experiences I became fascinated by the psychology of film and the film still. With education and experience in both disciplines I will explore in this dissertation the effect and affect of what is called the ‘cinematic’.

Laura Mulvey (2003) has written on the notion of the voyeuristic spectator in the movie theatre: the darkness; the projector that beams the light onto the screen; the structure of the spectacle and the desire to decipher the screen; the curiosity to see but also to know; the longstanding interest in puzzles and riddles. The obsession for screen images and stretching them into another dimension of time and place, she claims “no longer voyeuristic but fetishistic”. The slowing down and stilling process opens up new areas of fascination especially with the human presence in the city. The spectator is able to discover something that could never be seen at 24 frames per second. The camera is able to reveal more of the world than is perceptible with the human eye.

“No Picture could exist today without having a trace of film still in it, at least no photograph.” (Jeff Wall, 1996)

In my project In Company of StrangersI combine my fascination for the modern metropolis with the cinematic. I photograph city life in London with the apparatus of film, in order to capture the state of transit of city dwellers. This text analyses the cinematic quality of this project and especially its relation to film stills. I will discuss the notion of time and space, as they are the determining parameters for photography. The focus will be on the concepts of stillness and movement and I will describe the forms that lie in between. I will argue that photography, like film, is a time-based medium.

1: Literature review:

Photography & Film

In order to understand the ‘cinematic’ we need to trace its origins. The word cinema is derived from the French word‘cinématique’, from the Greek word ‘kinema’,which means thegeometry of motion. When we think about the ‘cinematic experience’ it is related to the illusion of movement that is to be studied in the history of the technique of film. This optical illusion is known as the ‘Phi Phenomenon’, first described by Max Wertheimer (1912). The human brain can perceive ten to twelve individual images per second; if sequences of images move faster than this the brain blends them together into continuous motion.

Cinema was introduced in 1895 by the Lumière brothers, sixty years after the rise of photography.Since the introduction of the cinématographe, photographers were the first to practise it. Early filmmakers like Sergei Eisenstein, Charlie Chaplin and Dziga Vertov were using photography as well. Photography has therefore been important for the sensibility of the development of the avant-garde film. Artists like Maholy-Nagy, Man Ray and Paul Strand made significant contributions to film. Urban photographers like Helen Levitt, William Klein and Robert Frank also used the medium of film.

From its inception, photography has been used in the fields of art and science. Because it was difficult to pin down its meaning, comparisons were often made with the disciplines of painting, theatre and cinema. This suggests that, painting puts the emphasis on questions of description and actuality, theatre emphasizes the performative and cinema emphasizes the ‘duration’ of the frame and therefore the notion of time. There is no other art form that is clearly the origin of cinema, it might be theatre, narrative painting or the flickering on the wall of Plato’s cave, but the only thing we can conclude is that we can trace it down to the depiction of movement (Campany, 2008).

To discuss the intersection of the fields of photography and film we should be aware of their threshold. To support my argument I will describe the three main differences between the two precisely.

The first difference is the size of vocabulary. Christian Metz (1985) described the spatial-temporal size of the ‘lexis’, the unit of reading and reception. A photograph has no fixed duration or temporal size; the spectator is the master of the look, whereas in cinema the filmmaker decides the timing of the cinematic lexis. If we compare it with literature, photography has a free rewriting time and cinema an imposed reading time.

The second difference is the social use. Film is associated with fiction and the public, photography is supposed to be real and private. Research of Pierre Bourdieu (1990) confirms that photographs are property; like souvenirs, something to keep for yourself. Film has always been oriented towards imaginary in the present, like a realist guarantee of the unreal, while photography is pointing to the print of what was, but no longer is. Roland Barthes (1980) refers to this as the ‘that-has been’.

The third difference is the materiality. Cinema results from an addition of features to those of photography: movement and the multiplicity of images. Every new image at 24 frames per second creates one and the same movement while in photography every new image creates a second movement (Zeno’s Paradox in Hugget, 2010). Movement and multiplicity implies time, while photography is considered timeless. Images in cinema seem to construct themselves in space as a stream of temporality where nothing can be stopped or kept. Cinema features five orders of perception: movement, multiplicity and three auditory ones: phonic sound (spoken words); non-phonic sound (sound effects) and musical sound. Photography only has two orders of perception: immobility and silence. Therefore photography is more connected to the timelessness of the memory and the unconsciousness(Metz, 1985).

Time & Space

The appropriate definition of the cinematic might be described in the Time-Image by Gilles Deleuze (1985). This theory draws heavily upon Bergson’s Creative Evolution(1911), which is a critique on clock-time. He introduces the term ‘duration’ as a subjective experience of time as opposed to mathematical, objectively measurable clock-time. Clock-time is a way of spatializing time therefore it is not really time: it is a form of space. This can be best understood through creative intuition, not through intellect.Actual lived time is time that flows, time in which the past and future penetrate into the present in the form of memory and desire. Time slows down when we are bored and speeds up when we experience stress. We forget time when we dive into our memory, fantasy and dreams.

For Bergson, the present is a dynamic interpenetration of past and future. Our lived world that is here for us right now, is what he calls the ‘actual’. When we enter our memory or fantasy, we leave the present for the past or future, and live mostly in the realm of the ‘virtual’. In his theory, time is divided over, what in math would be, two axes: the x-axis that is horizontal and represents ‘objective time’, and the y-axis, that is vertical and represents ‘subjective time’. The closer one is to the x-axis, the more one is in the here-and-now, which is the actual. The more one expands on the y-axis the further one dips into the past or future, the there-and-then, the virtual. Any image that brings us further up the y-axis, which helps us recognize, recollect or dream, is a type of time-image.

When Bergson (1896) in Matter and Memory, and Deleuze (1985) inThe movement imagetalk about ‘images’ they do not necessarily mean photographs or films. It is a way of seeing and interpreting the world, it can be an idea, concept or story, therefore we communicate with images. Deleuze describes the perception, affection and action image, which I will discuss later in relation to my project.

City & Cinema

Film is an ongoing source of inspiration for architects. They realise the city has a narrative to it that evokes a cinematic experience (Penz, 2011). To study cinema in relation to the city we can discover the ‘soft side’ of the city (Raban, 1974). The soft side of the city is how we imagine it: illusion, myth, aspiration etc. It is as real, maybe even more real, than the hard city, the concrete world created by architects. Understanding these complex urban issues can help urban planners in the future.

In film, cities are used as stages on which the narrative develops; they function as the arena for the story. Often the city is presented as a personality that sets the mood for the film; think Vertigo’s San Francisco, Scorsese’s New York or the fictional cities in Metropolis and Blade Runner. Most of these films are concerned with the shocking newness of the modern city, like new technologies in communication and entertainment and new behavioural patterns of its inhabitants (Sjöberg, 2011). In most of these films, the fragmented, montage like experience of the man in the modern city is central.

The theories that developed at the rise of modern cities were as eclectic as science fiction films. I will elaborate on them in the appendices of this text. Most of them reveal the sensitive, emotional perspective of the city. The city is the ultimate place for endless cinematic imagination.

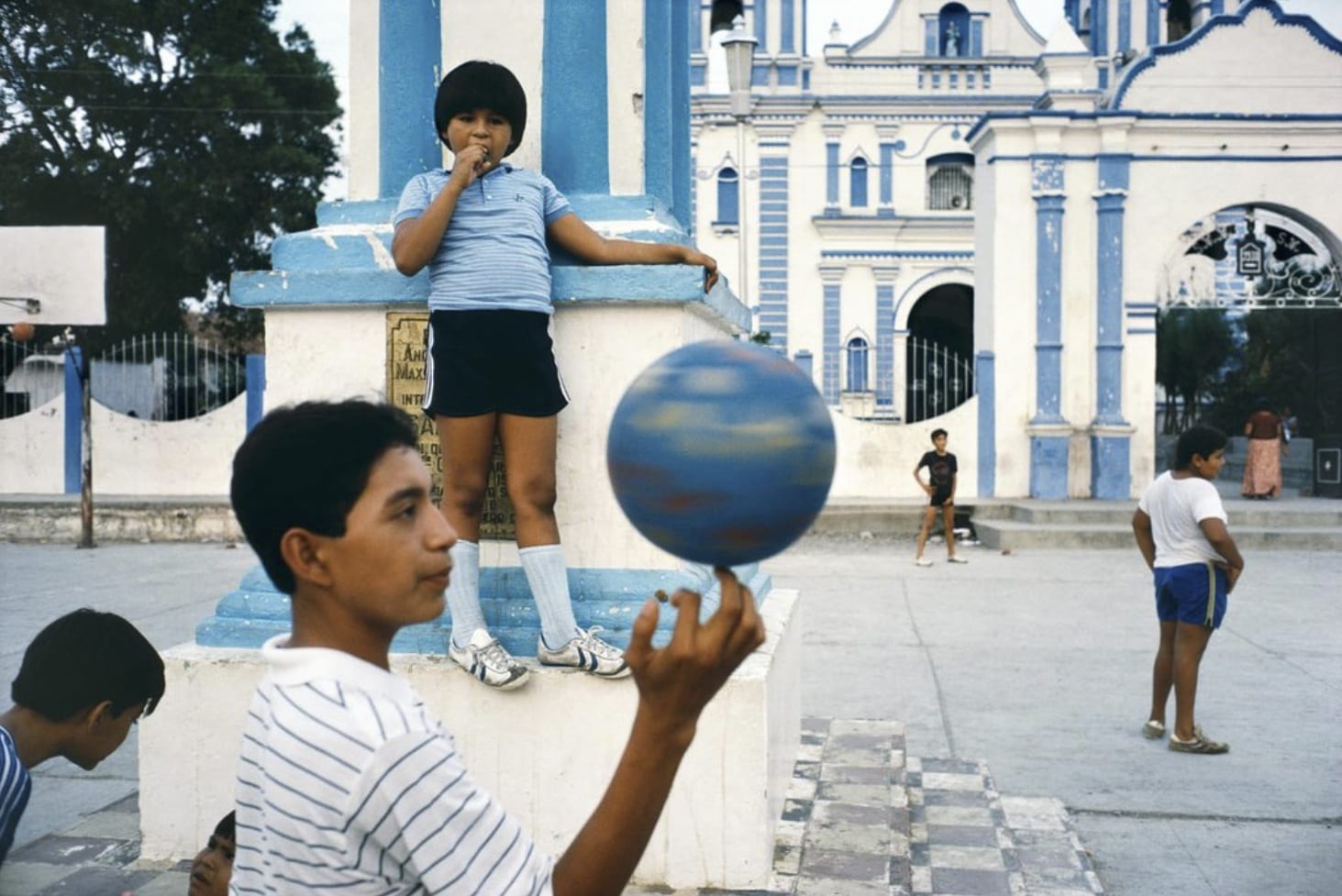

Figure 1. In Company of Strangers (2015) Bas Losekoot

Figure 1. In Company of Strangers (2015) Bas Losekoot

2: Methodology

The modern metropolis of London is the stage for my project In Company of Strangers. Istarted this project at the beginning ofthe Urban Millennium; the day more people were living in cities than in rural areas, that is 3.3 billion people on three percent of the earth’s surface (UN, 2007). We are currently facing the biggest wave of urbanization in human history. This fact made me wonder how this growing population density is going to influence inhabitants of cities. This project is an exploration of the role of the individual in the densely populated city of London.

I am interested in exploring what the notion of ‘progress’ of the city means on a human scale. Therefore I photographed people that have to engage with this progress: everyday working people. I photographed them in places where they commute. I positioned myself in places where personal space is condensed by others, close to entrances of offices and tube stations. I am drawn to places where this progress is literally in the making, for example close to construction sites. The artist impressions used to advertise the new developments are part of the ‘promise’ of the city. The locations I worked in are selected on the following elements: population density, proximity of people and the level of energy and dynamics on the street. I choose the high-pressure areas of the city, where emotions come to the surface. Because I photograph people in ‘transit’ I am drawn to the liminal spaces of the city. It is important to understand that my focus is on the psychological effects of urbanisation, therefore it is not about the city, moreover city-life. The project is not specifically about London; it is emblematic of the modern metropolis.

Figure 2.In Company of Strangers (2015) Bas Losekoot

Figure 2.In Company of Strangers (2015) Bas Losekoot

I carefully observe behaviour at a location before I start photographing. I often return to the same place. I photograph all day, but I am especially active during the morning rush in the winter and evening rush in the summer. I install flashlights on tripods and onto anything that I can find on the street, on order to create a mixture of natural and artificial light. I shoot hand-held. I position the light and then wait for the people to walk into the frame. I use the ‘fly on the wall’ technique. I don’t like to be noticed and I try to blend in as much as possible. I want to catch people unaware of being photographed. I never talk to people; I avoid eye contact before the shutter is released. Afterwards I nod and smile friendly to the ‘actors’.

I use a digital 135mm camera. I crop my images with the more widescreen image ratio of 1.64:1. The series can be divided into three different types of frames: wide-angle shots that are about the relationship of the individual with their environment, medium-angle shots that are about the interaction between individuals, close-up shots that are zooming in on the state of mind of a certain individual and extreme close-up shots that create a ‘larger than life’ reality.

3: Analysis

The relationship of photography to the cinematic is based upon two considerations. On one hand photography is a ‘technology’, an instrument that stops time through the mechanism of the shutter. On the other hand it is a ‘medium’ that deals with temporality and therefore is representing time. The distinction between technology and medium is intertwined and the difference is not always clear. How can we think about photography as a technical process rather than its representational function? Or how can we discuss the representational and aesthetic qualities without recognizing the process of technical production. According to Walter Benjamin (1931), this imposition of the technology of photography upon the subject, inadvertently exposes a deep subjective relationship to movement and stillness. All the images of In Company with Strangersare made at 1/250 second. The flash emphasizes the capacity to freeze a moment in time. It creates an uncanny (Freud, 1919) feeling that is close to the sublime (Burke, 1756). Roland Barthes (1980, p. 49) refers to this feeling as the notion of now-ness; “it seizes a reality that is there, that was there, in an indissoluble now; a basically uncontrollable experience, that which takes place only once”.

Figure 3. Street (2013) James Nares

Figure 3. Street (2013) James Nares

The notion of an instant is one of the foremost qualities of photography. In a blink of an eye, it cuts, immobilises and fixes life. The frozen moment emphasises that human gestures are highly ephemeral and unpredictable. “It suspends movement, petrifying the real, and reveals that immobility is a relative impossibility” (Mah, 2010, p.10). When gestures on the street are frozen they transcend time. The moment depicted becomes an extended moment (Nares, 2014). It is a film duration that is referred to as the ongoing moment by Geoff Dyer (2012). The instant is alive with time and motion.

To me frozen moments are charged with suspension. They visually convey certain elements that transfer themselves to the mind of the audience (Hitchcock, 1970). These images suggest something that needs to be revealed by the imagination of the spectator. I refer to this magic of photography as the suspense of movement.

Figure 4. In Company of Strangers (2015) Bas Losekoot

Figure 4. In Company of Strangers (2015) Bas Losekoot

Film stills are images that are made by a stills photographer on the set for promotional purposes. For many years I worked as a stills photographer on film sets of Dutch feature and television films. Film stills merely function in relation to the film. They are not intended to be looked at for a long time or to stand on their own. To encounter a printed film still without knowing the film is interesting. In the 1970’s television became increasingly popular and film studios no longer wanted to archive film stills of old movies, so they relegated them to second-hand shops (Campany, 2008). These informal archives were thought to have little value. The images were thrown into a new context, cut off from their sources; their meaning was there for grabs of the finder. What sense do we make of an image when we do not know where it has come from? The beauty and the craft of the image are robbed of the reason. In that sense they regard the potential fate of any other photograph without a context.

Figure 5. In Company of Strangers (2014) Bas Losekoot

Figure 5. In Company of Strangers (2014) Bas Losekoot

Figure 6. American Psycho (2000) Mary Harron

Figure 6. American Psycho (2000) Mary Harron

Freeze frames

Still photographers have always been a luxury for film productions. The alternative is the freeze-frame: to capture images from the original film footage, by re-photographing a screen or projection or nowadays by computer screenshot. These images lack the technical quality compared to those off the still photographer but were appreciated for their authentic look. The freeze-frame is an encounter with an absence, like a revenge on cinema. “It reveals the untruth of the film still as a simulacra of the cinematic moment” (Campany, 2007). Cinematic images arouse the desire to keep; to freeze a film and reproduce it is possibly a desperate way to own a film. The film still stands for this impossible desire: to hold onto what, by its nature, is designed to disappear (Stezaker, 2008).

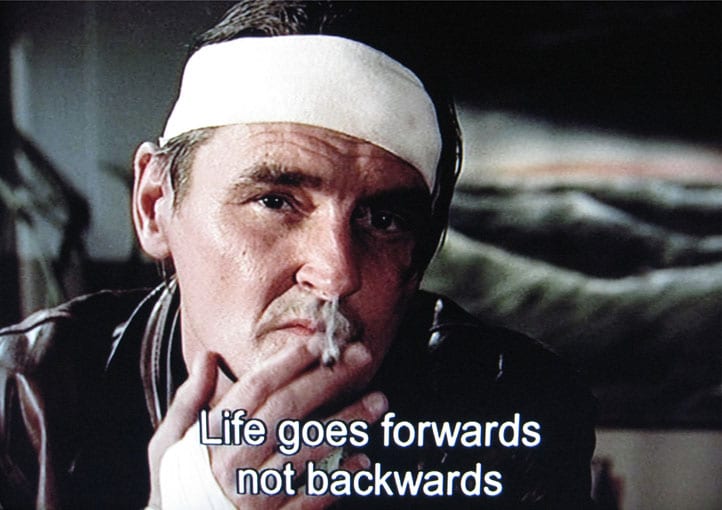

Figure 7. The Man Without a Past (2002) Aki Kaurismäki

Figure 7. The Man Without a Past (2002) Aki Kaurismäki

The fascination with film stills is explored by Roland Barthes (1973), who was in search of ‘the third meaning’ in his essay on stills of Eisenstein’s films. He was interested in the idea that the single film frame contains more potential meaning than we are able to see at 24fps. When watching a film we focus on just a small element of the image on the screen, usually the things that move. When looking at a single frame we have time to inspect every little detail. Barthes notably argued that what was truly cinematic about film revealed itself only when the film was deprived from movement.

This idea, that we can only comprehend the cinematic quality of film when the film is stilled, was appealing to me when developing my project.

Figure 8. Glove 2 Part 1 (2006) John Stezaker

Figure 8. Glove 2 Part 1 (2006) John Stezaker

For Barthes an image could be cinematic without being in a film. It can have a narrative without being in a narrative. Film stills are rich in association and full of dramatic possibilities. My images combine the freeze-frame/extracted film frame and film still/staged photograph. Based on the dramaturgical approach of Ervin Goffman (1959), I consider the street, the stage where we, as the actors perform with the city as décor.My images are part of the story of the city. I attempt to load them with information to activate the viewer to imagine what happened just before or after the shot was taken. This can be achieved by gesture, expression or suggesting an event happening just outside of the frame (off-screen event)

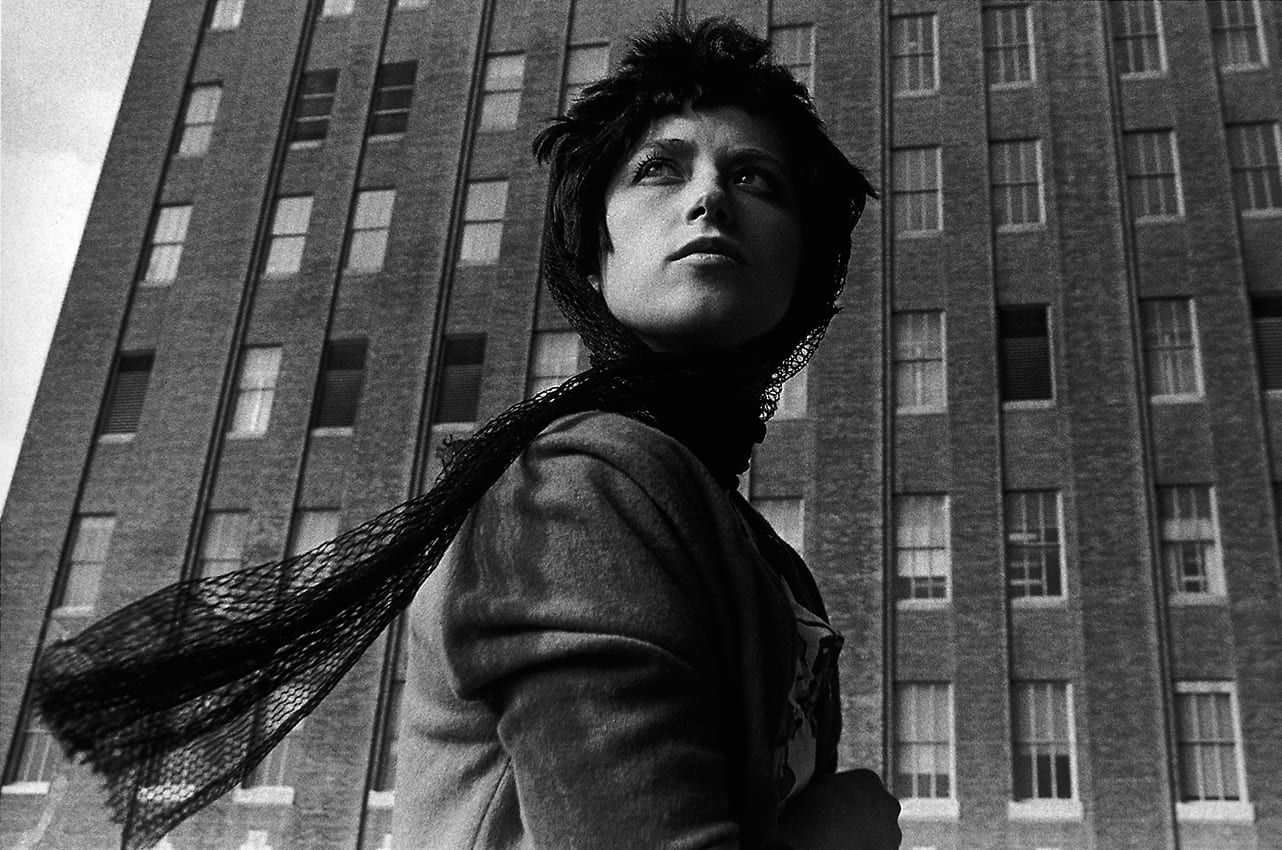

Figure 9. Untitled Film Still #58 (1980) Cindy Sherman

Figure 9. Untitled Film Still #58 (1980) Cindy Sherman

On the street I install flashlights to add a heightened drama to the images. Sometimes I use them to isolate people from the background, or to light the facades of buildings. This creates a new reality in everyday life situations, an uncanny hyper-reality that forces the viewer to revise the ordinary and discover the extraordinary. This use of light is inspired by the double light situations created by mirroring windows from high-rise buildings. The light expresses the life in the urban jungle that can be seen as a human zoo (Morris, 1969).

“It is decisive that city life has transformed the struggle with nature for livelihood into an inter-human struggle for gain, which here is not granted by nature but by other men” (Simmel, 1950, p. 420)

I argue that where we normally had to run for our lives we now have to run for our jobs. We are not running for life-threatening danger but danger for exclusion. The struggle for survival remains the same. Because the ‘city animal’ does not get the time to adapt genetically to this modernity, we are experiencing high levels of stress. (Morris, 1969).

Figure 10. In Company of Strangers (2015) Bas Losekoot

Figure 10. In Company of Strangers (2015) Bas Losekoot

Based on Bergson (1896), Deleuze (1983) outlines thatperceptionscause affections and affectionscause actions. He distinguishes three types of movement-images: perception images (wide angle shots, point of view), affection images(close up shots, expression of feelings) and action images(medium shots, focus on duration of action)(Parr, 2005).In my work I use wide-angle shots to establish the narrative. This places the viewer in the story and location in the city. I use medium-angle shots to capture collisions of people on the street. They engage with each other because I bring them together in the frame.Recently I started to experiment with extreme close up images to create an extra, contemplative and meditative layer to the work. The people depicted become the protagonists of the story. I photograph people while they seem lost in thought, detached from the actual. Their inward gazes seem to reveal a micro-drama. Deleuze describes the close ups of faces like “wholes that are cut off from the space and time around them; they bring forth the fear of the obliteration of the face. However, desire and wonder give them life”(Deleuze, 1983, p.110)

Figure 11. Women in Thought (1950) Harry Callahan

Figure 11. Women in Thought (1950) Harry Callahan

Figure 12. In Company of Strangers (2015) The Author

Figure 12. In Company of Strangers (2015) The Author

Apart from the technique: what is the cinematic effect and affect in my work? The position of the camera is usually at knee height, which indicates a third person perspective and refers to the perception image used in film. I use a long tele-lens to compress people with high-rise buildings. I often use it to condense unrelated people with each other to underscore we are in company of strangers. To emphasize the human zoo I rarely include the sky in my photographs. I do not place people in the frame but try to find the right ‘mise en scène’ for the composition, by following people’s movement in the frame and pre visualize the scene. Lately I have experimented with images of people photographed from behind. The individual depicted becomes first person in the scene; we start to see the world from their point of view. An important difference from the work of Philip-Lorca DiCorcia, Gregory Crewdson and Beat Streuli is in the seriality of my work. I combine wide, medium and close shots in one narrative photo-essay that is edited as in classical film montage. I consider my images to be part of a continuum.

Figure 13. Tokyo 98 II, 41_52 (1998) Beat Streuli

However the cinematic quality of my images is not only a method matter but a subject matter as well. I photograph people on the move, in transit, mostly commuters. I consider junction points in traffic to be metaphors for the junction points in the human psyche. The city functions as a pressure cooker for human emotion and expression. I try to capture it at the speed of life. I like to see the many brief moments of eye contact as a continuous stream of split-second meetings.The gestures and expressions I photograph refer to past experiences of the actors, like a flashback sequence in fiction film. My images are disquieting fragments that combine elements of loneliness, beauty and desire. I aim to create an unreal, theatrical effect in my images. We are currently living in a time where mobility, instantaneity and simultaneity define our modes of live. In the public domain we hide behind protective screens,such as sunglasses and headphones, and stare at mobile telephones. Through technology we are able reduce time and space (Gordon, 2010). Our lives are formatted by technology. On the street we are physically present but mentally absent. I attempt to capture people that are alienated from reality. I focus on objects we use to protect ourselves from contact with strangers.

Figure 14. In Company of Strangers (2015) Bas Losekoot

Figure 14. In Company of Strangers (2015) Bas Losekoot

4: Discussion

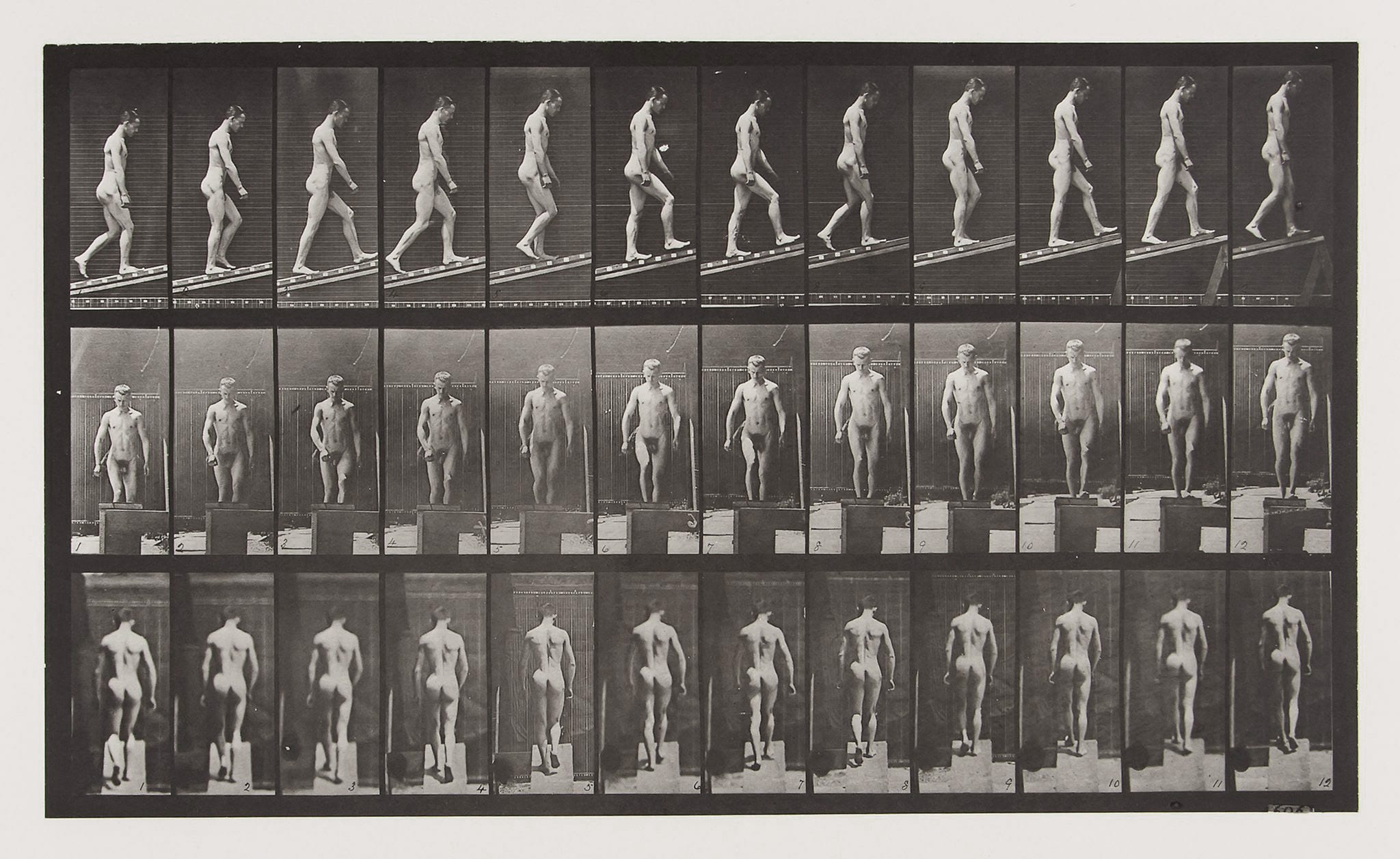

Film creates its own time, photography stops time (Newhall, 1937). Film is like a line; photography is like a point (Wollen, 1984). The debates around film and photography are dominated by the concept of time. Stopping time was the goal of Edweard Muybridge and Etienne-Jules Marey at the end of the 19thcentury. Muybridge is famous for his ‘chronophotographs’ in which he captured movement with stop-motion. He used multiple cameras in a row to record sequences of human and animal locomotion and presented the photographs in a grid. It was as if the images were waiting for motion to occur. Marey produced multiple images on one single photographic plate. The images appear like translucent layers on top of each other. Both pioneers were interested in decomposing movement to examine its frozen forms. Nowadays the work of these chronophotographers is seen as the parent of cinema, not photography.

Figure 15. Animal Locomotion, Plate 74 (1878) Edward Muybridge

Figure 15. Animal Locomotion, Plate 74 (1878) Edward Muybridge

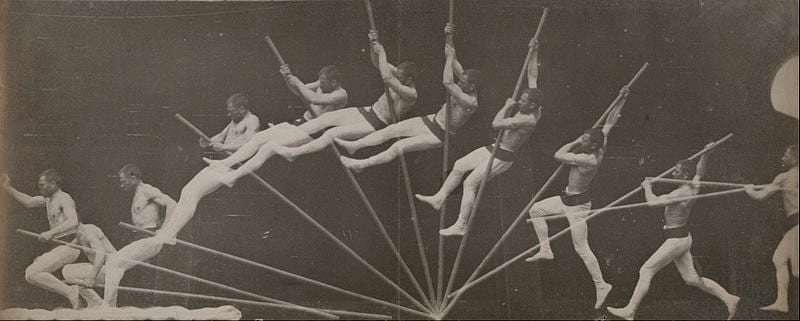

Figure 16. Movements in Pole Vaulting (1985) Etienne-Jules Marey

Figure 16. Movements in Pole Vaulting (1985) Etienne-Jules Marey

Muybridge and Marey lived long enough to encounter the Lumière Brothers, but they were indifferent to the new medium of cinematography. Marey even told the Lumières that their cinematograph was of no interest to him because it merely produced what the eye could see, while he sought the invisible (Campany, 2008). This is the essence of my photographic practise: like Muybridge, I stop time to study the frozen instant. My use of light is merely a way to emphasize the capacity photography has to freeze a moment. I use the arresting shutter to reveal things that otherwise can not be seen with the naked eye. I photograph people in order to really seethem. I adopt the precise qualities and sharpness of the optics of photography.

“For me the noise of Time is not sad: I love bells, clocks, watches – and I recall that at first photographic implements were related to techniques of cabinet making and the machinery of precision: cameras, in short, were the clocks of seeing…” (Barthes, 1980, p. 15)

Figure 17. In Company of Strangers (2015) Bas Losekoot

Figure 17. In Company of Strangers (2015) Bas Losekoot

In cities we can experience the circle of time, for example in train stations the site of departure is often the site of arrival. They are often depicted in film as a place of transit as well. Travel and motion in the city is a heightened experience of space through time that is similar to the image rush in cinema (Webber, 2008). I have chosen sites of transit, the non-spaces(Augé, 1995) as the backdrop for my images because they depict the mobilities in the city. They are liminal spaces that represent moments of in between-ness of city’s inhabitants. The cinematic city is a palimpsest of stories and lived experiences. Travelling the city is like editing a film; a journey of transmission of affects. In both cities and film we experience motion that is actually the energy of emotion. Camera movements are often used as a change of viewpoint but also, a change in a narrative. Motion pictures not only move us through time, but also move us through inner space. “In the city, as when travelling with film, one’s self does not end where the body ends nor the city where the walls ends, the borders are fluent” (Bruno, 2008, p. 25).

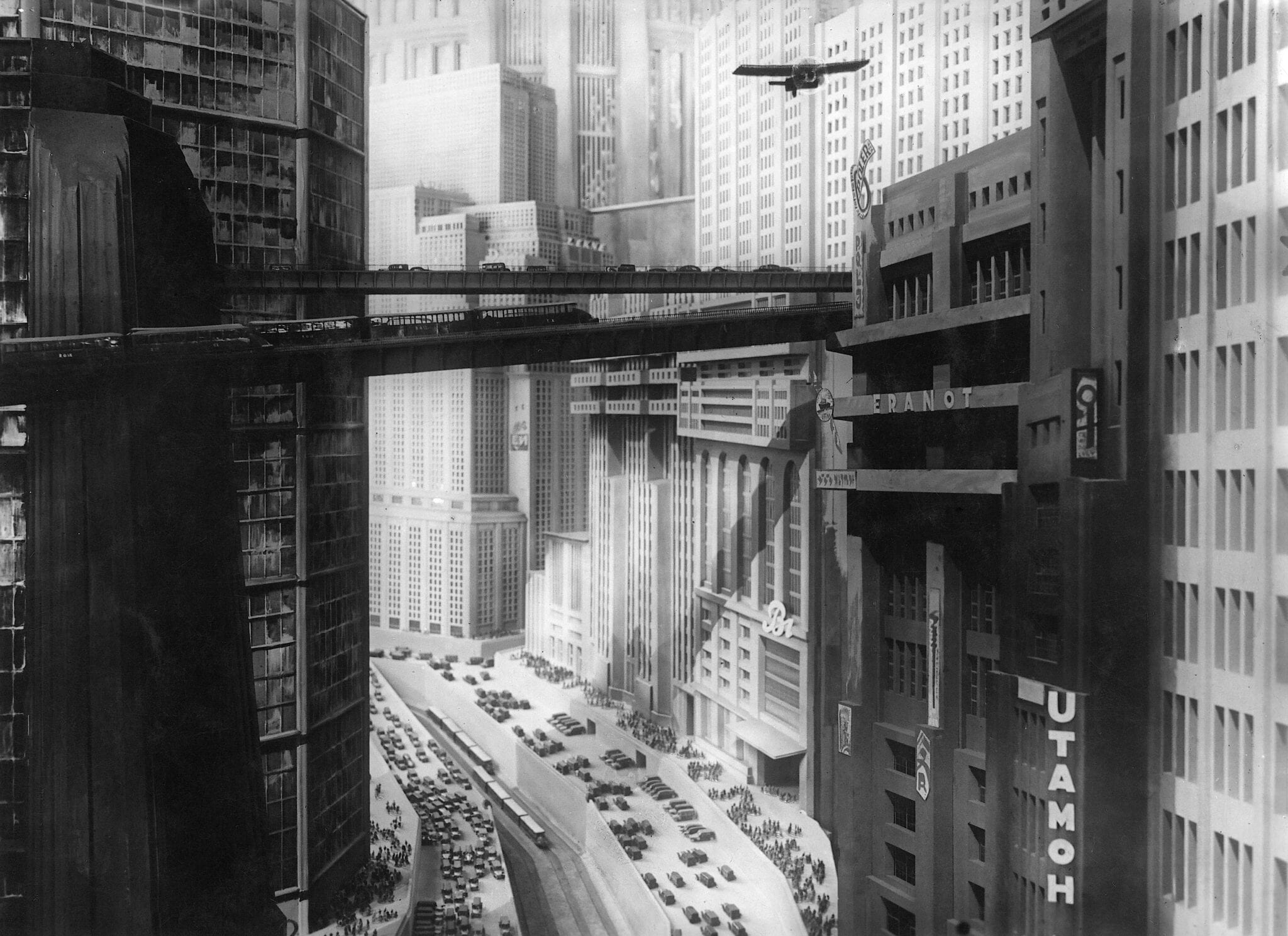

Figure 18. Metropolis (1927) Fritz Lang

Figure 18. Metropolis (1927) Fritz Lang

The moving image has impacted upon our ideas of the modern city. Cinematic affect shapes and reflects our socio-cultural sensibilities. My project was once critiqued for being dystopian. Our ideas on the past and future of cities are inseparable from the production and circulation of images. Films often draw the future of cities as a world of darkness, crisis and catastrophe (Prakash, 2010). Dystopic imagery has figured prominently in the depictions of the modern urban landscape. I am undisputed affected by these films, though I never alter or adjust reality towards this imagery. Besides the artificial light I consider my work to be documentary photography and my message is a critical one: urban development does not equal human development: Are we creating ideal cities by building these mega agglomerations? With my project I hope to raise awareness of this issue through cinematic vernacular.

Figure 19. In Company of Strangers (2014) Bas Losekoot

Figure 19. In Company of Strangers (2014) Bas Losekoot

Film and photography are both characterised by the inherent tension between stillness and movement. Gilles Deleuze’s distinction in film theory of the movement-image and time-image implies that these are separate things. I argue that the majority of film theory can be applied to photography and vice versa. To equate movement with film and stasis with photography would be a mistake. That would confuse its representation with its material support. A film can record and immobile object when the filmstrip is moving at 24fps and a photograph can record a moving object in a single frame, and there is a myriad of forms in between. Activity is not necessarily connected with movement, for example when people read a book in a film. Photography is not about stillness and film is not aboutmovement, nevertheless stories tend to choose the medium that technically fits them best.

A great example of movement versus stillness is, the work of art that gave rise to my cinematic imagination, Chris Marker’s La Jetée. This is a film composed of still photographs, only one brief moment, an actual blink of an eye, is film footage. Here Marker is inverting the notion of instant and duration. The arena of the story is a place- and timeless limbo. “It is the form best suited to express the tension between stasis and momentum, between the weight of memory and the possibility of a future” Campany, 2008, p.100)

Figure 20. La Jetée (1962) Chris Marker

Figure 20. La Jetée (1962) Chris Marker

5: Conclusion

Photography stops time. It freezes moments with its arresting shutter. These frozen moments are alive with suspense of movement and convey an experience of duration similar to what we experience in the cinema. Photography is a time-based art form in the sense of spectatorship, considering the time the viewer spends with the photograph. Its impact is continued afterwards in the sense of the extended and ongoing moment. Therefore we can assume photography to have four dimensions as in film. Photographs give us the ability to locate time, recognize and archive it (Baetens, 2010). This in order of our pursuit of controlling time, a sublime ambition that derived from our fear for death.

The slowing down and stilling process of film opens up new areas of fascination especially with people in the urban environment. Cinema is a medium of revelation. Imagine a film that starts with a photograph, the moment the image starts to move and comes to life is where the magic of cinema infuses the screen. As the image is stilled again, a new fascination comes into being: the new insight into the old narrative (Mulvey, 2003). The spectator is able to discover something that could never be seen at 24fps. The camera can reveal more of the world than is perceptible with the naked eye.

The city is one of the great protagonists in cinema. Moving images helped cities creating their ‘personality’ (Gaiman, 1993). In the city we find movement, rhythm, and change. The city is a metaphor for cinema. Travelling the city can be an utterly cinematic experience (Hollander, 2013). The city is a stratification of possible histories and stories, a real time machine (Wells, 1895). Cinema mediates our perception of time and space in the city. “To understand the city as a psychological and cinematic place helps to bring people together in the future in a way that makes a difference to what goes on between them (Pile, 1999).Rem Koolhaas (1978) described Manhattan as a place built as an impossible truth. We don’t believe our eyes when we see the Flatiron Building, yet it is real. The city is a cinematic dream factory that attracts people with vast expectations. The promise of the city is the escape to the future.

“Our contemporary life as it is would be completely different if the 20thcentury had happened without cinema – our habits, the way we look, what we do, what we think would be different – our contemporary life now in the 21stcentury is completely formed by the fact that the 20thcentury was the century of the moving image – the moving image changed our way of thinking, moving around and seeing things” (Wim Wenders, 2003 cited in Penz & Lu,2010)

Figure 21. Written in the West (1983) Wim Wenders

Figure 21. Written in the West (1983) Wim Wenders

Finally then, what isthe cinematic? I propose the cinematic is an affect thatconnects us to another perception of time and space. It is an unconscious reaction to a sign in photography, film, art or daily life in the city (Niedich, 2003). To analyse this with the Deleuze’s theory on cinema (1983, 1985), it is a sign that creates an image infused with time and movement. This is an image, which is different from itself and virtual to itself. It is the moment we move from the x to the y-axis on the time line, from the present/actual to the past, future/virtual. These are moments of travelling in which we get carried away in a train of thoughts and feelings, like in a memory, fantasy or dream. The cinematic experience is what Deleuze would describe as an affection image: wholes that are cut off from the space and time around them. In my photographs I consider the cinematic to be the ‘suspense of movement’. I try to charge my images with information that makes one wonder what happened shortly before this frozen moment, or is yet about to happen. Photographs tell us more than they show us. The invisible is just as important as the visible.

This dissertation has shed light on the influence of the cinematic on the spatiality and temporality of still images. I have traced my own process and results of the making of the series In Company of Strangers. This text endeavoured to unfold and discuss the motivation, inspiration and subject matter of this project in relation to the cinematic. Rethinking these issues in a wider theoretical framework has led me to a better understanding of the apparatus of film and photography. I have interpreted my research and constructed my argument through the application of photography, film and urban theory as well as ideas borrowed from the fields of philosophy and psychology. I have become more aware of the cinematic impact and affect on the city and my urban photography practice.

Roland Barthes (1986) wrote about that strange transition we experience when a film is over, in his essay Leaving the Movie Theatre. Our bodies awake and our minds need to switch from one reality into another. As we leave the cinema our memory starts to edit a new film.

Figure 22. Movie Theatre (1980) Hiroshi Sugimoto

Figure 22. Movie Theatre (1980) Hiroshi Sugimoto

6: Appendices:

Urban theory

Guy Debord (1955) emphasizes playfulness and drifting in a space with his concept of ‘psychogeography’. He studied the immediate experience of the city and its implications for human emotion. Edward Soja (1996) is concerned with the ‘instability of the globalised society’. He argues that pre-existing urban realities are going to be re-territorialised and re-colonalized in a way that does not correspond with the sense of place of social communities. He predicts difficulties separating the interior from the exterior and the suburban from the metropolitan. Lisa Parks (2005) is researching the influence of images made by satellites on our society. With invisible technologies we are able to make ‘god-like’ images of the surface of the earth’. She argues that Google Earth influenced the way we relate and interact with the real world. Walter Benjamin (1938) writes about the ‘pleasures of being lost’ in a city.

“Not to find one’s way around a city does not mean much. But to lose one’s way in a city, as one loses one’s way in a forest, requires some schooling. Street names must speak to the urban wanderer like the snapping of dry twigs, and little streets in the heart of the city must reflect the times of day, for him, as clearly as a mountain valley. This art I acquired rather late in life; it fulfilled a dream, of which the first traces were labyrinths on the blotting papers in my school notebooks.”

Based on the Baudelaire’s ‘flâneur’ (1863), he proclaims getting lost as a form of art.Getting lost in a city produces a sense of reflective distance and a heightened sense of presence. The sensation of a site has nowadays become a mediated experience. Steve Pile (2005)argues that the imaginary the fantastic and the emotional must become part of the real politics of the city. “To understand the city as a psychological and cinematic place helps to bring people together in the future in a way that makes a difference to what goes on between them” (Pile, 1999).He emphasizes the city as a visceral bodily experience with ‘phantasmagorias’ like vampire, ghost, dreams and magic.

If we sum up the notions of psychogeography, instability of the globalised society, god-like images of the surface of the earth, pleasures of being lost and phantasmagorias, we have the appropriate ingredients for a fiction film.

The decisive moment

Compared to film, photography is limited. I consider this limitation to contain an exciting challenge, to seize the essence of a story in a still image.

“I prowled the street all day, feeling very strung up and ready to pounce, determined to ‘trap’ life, to preserve it in the act of living. Above all I craved to seize the whole essence, in the confines of one single photograph, of some situation that was in the process of enrolling itself before my eyes”. (Cartier-Bresson, 1952, p.2)

Figure 23. In Company of Strangers (2015) Bas Losekoot

Figure 23. In Company of Strangers (2015) Bas Losekoot

In this quote lies the root of his theory of the ‘decisive moment’. He argued that there is one singular perfect microsecond to release the shutter. This is actually best understood by another quote of the same book: “Photography is the simultaneous recognition, in a fraction of a second, of the significance of an event as well as of a precise organisation of forms which give that event its proper expression.” Cartier-Bresson has produced lots of images in which we feel the fast shutter: the arrested time. He combined this with an outstanding sense of space. He shot hundreds of magical moments because he was able to time and frame very quick and precisely. Like a nervous cat he operated focus, aperture and shutter speed; colliding and colluding with the world in motion (Duve, 1978). The frame cuts into space and the shutter cuts into time.

Figure 24: The Decisive Moment (1952) Henri Cartier-Bresson

Figure 24: The Decisive Moment (1952) Henri Cartier-Bresson

Geometry in composition was something that Cartier-Bresson was always looking for. In his compositions he liked to instinctively fix a geometric pattern in which his subject fitted. He would wait for someone to walk into a pre-composed frame. I can relate to this since I have to work from one fixed place as well, not because of a locked camera but fixed lighting installation. Before I set up the light I choose a composition that keeps me, more or less, in the same position. The only thing I can do is hope for the right person at the right time and place.

Figure 25. Istanbul (1998) Alex Webb

Figure 25. Istanbul (1998) Alex Webb

Clock

Industrial capitalism assigned complex manual tasks to the automatic operation of machines. It introduced the global use of the clock and the development of photo cameras was flourishing because of this. Its main task was recording appearances as a record of reality. Which seems to us slightly outdated. Nowadays we assume that the camera only creates a record of a moment in time. It is a spatialization of temporality to clock time (Burgin, 2010) Series of photographs are stories placed in a circle of time; the circle is not perfectly round but ellipse. For example, Deleuze (1982) distinguished two kinds of film directors: ones that are only interested in the middle of the story and ones that are only interested in the beginning and the end. Films are circles in time too; the beginning and the end are the same thing. It is in the same movement in which the world is born and ends.

Frame rate

The standard frame rate for film is 24fps. Digital filmmakers try to push the temporal resolution of the image to 48 frames per second, to decrease motion blur and increase smoother movement in effort to create a more realistic look. A similar experiment took place in the 70ies when filmmakers started to experiment with 70mm film stock and projecting it at 60fps. What is interesting here is that film technicians try to achieve in cinema what I try to achieve with photography: capturing reality in a way that can not be captured with the human eye. Same like my frozen images; higher frame rates create an uncanny (Freud, 1919) hyper-reality. Audiences of narrative film were not positive about this and critiqued it as too sharp, too smooth and unreal. This example demonstrates the nostalgic affect of cinema, audiences don’t like clarity and smoothness, they want old-fashioned dust, grain, and motion blur.

Figure 26. In Company of Strangers (2015) Bas Losekoot

Figure 26. In Company of Strangers (2015) Bas Losekoot

References

Augé, M. (1995) Non-Places: Introduction of an Anthropology of a Supermodernity.London: Verso.

Baetens, J. & Streiberger, A. & Van Gelder, G. (2010) Time and Photography.Leuven: Leuven University Press.

Barthes, R. (1970) The Third Meaning: Research Notes on some Eisenstein Stills[Online Video]. Available from:http://thethirdmeaning.blogspot.co.uk/2007/10/roland-barthes-third-meaning.html[Accessed August 2015].

Barthes, R. (1980) Camera Lucida, Reflections on Photography. France: Vintage.

Barthes, R. (1986) Leaving the Movie Theatrein The Rustle of Images.Oxford: Blackwell.

Baudelaire, C. (1863)The Painter of Modern Life. Boston: Da Capo Press.

Benjamin, W. (1938) A little History in Photography. Cambridge: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press.

Benjamin, W. (1999) On some motives on Baudelaire, in Illuminations. London: Pimlico.

Benjamin, W. (1999) The work of art in the age of mechanical reproduction, in Illuminations. London: Pimlico.

Bergson, H. (1896) Matter and Memory. New York: Zone Books.

Bergson, H. (1911) Creative Evolution.New York: Henry Holt and Company.

Blader Runner(1982) [Film] Directed by Ridley Scott: USA: Warner Bos

Bourdieu, P. (1990) Photography, A Middle-brow Art. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Burgin, V. (2010) The Eclipse of Time,in Time and Photography. Leuven: Leuven University Press.

Burke, E. (1756) A Philosophical Enquiry into the Origin of Our Ideas of the Sublime and Beautiful, in Dictionary of the History of Ideas. (1974) New York: Charles Scribners & Sons.

Bruno, G. (2008) Motion and Emotion: Film and the Urban Fabric,in Webber, A. & Wilson, E. (eds) Cities in in Transition: The Moving Image and the Modern Metroplis.London: Wallflower.

Campany, D. (2007) Two Memories and a Reflection inJohn Stezaker Film Still. London: Ridinghouse.

Campany, D. (2008) Photography and Cinema. London: Reaktion Books Ltd.

Cartier-Bresson, H. (1952) Image à la Sauvette, Göttingen: Steidl.

Debord, G. (1955) Introduction to a Critique of Urban Geography, inLes Livres Neus. Paris: Editions Allia.

Deleuze, G (1983) Cinema 1: The Movement-Image. London: Continuum.

Deleuze, G (1985) Cinema 2: The Time-Image. London: Bllomsbury Publishing Ltd.

De Duve, T. (1978) Time Exposure and Snapshot: The photograph as paradox, October, 5, pp. 113-25. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Doane, M. A. (2002) The Emergence of Cinematic Time: Medernity, Contingency, the Archive. Cambridge: MA Press.

Dyer, G. (2012) The Ongoing Moment.New York: Canongate Books Ltd.

Freud, S. (1919) The Uncanny.London: Hogarth.

Gaiman, N. (1993) A Tale of two cities, The Sandman, 8. New York: DC Comics. pp 18-41.

Gibbons, F. (2011) Jean Luc Godard: ‘Film is over. What to do? [Online]. Available from: http://www.theguardian.com/film/2011/jul/12/jean-luc-godard-film-socialisme[Accessed August 2015].

Gierstberg, F. (2010) Documentaire nu! Hedendaagse strategieën in fotografie, film en beeldende kunst,Rotterdam: NAI Publishers.

Gordon, E. (2010) The Urban Spectator: American Concept-Cities From Kodak to Google. Lebanon: University Press of New England.

Hollander, J. D. (2013) The city as time machine, [Online] Available from: http://affr.nl/articles/the_city_as_time_machine.html [Accessed August 2015].

Huggett, N. (2010) Zeno’s paradoxes: 3.3 The Arrow. [Online] Available from: http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/paradox-zeno/#[Accessed August 2015].

Koolhaas, R. (1978)Delirious New York: A Retroactive Manifesto for Manhattan.New York: The Monacelli Press.

La jetée(1962) [Film] Directed by Chris Marker. France: Argos Film.

Latif, T. (2004) Subtitles of Life and Death. Photographs by David Barette. (selfpublished).

Lefebvre, H. (1992) Rhythmanalysis. Paris: Éditions Syllepse.

Lessing, G. E. (1766) Laocoon, (eds.) Laocoon, The Wise, N. & Von Barnhelm, M. London: J. M. Dent & Sons

Mah, S. (2010) Between Times: Instants, Intervals, Durations.Madrid: La Fabrica

Metropolis(1927) [Film] Directed by Fritz Lang. Germany: Universum Film A. G.

Metz, C. (1985) Photography and Fetish, October, 34, pp. 81-90. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Michelson, A. (1990) The kinetic icon of the work in mourning: Prolegomena of the analysis of textual system, October, 52, Cambridge: MIT Press, p. 22.

Motion Study(2015) Corbis Contributor [Online] Available from: http://forum.contributor.corbis.com/motion-study/[Accessed August 2015].

Morris, D. (1969) The Human Zoo. New York: McGraw-Hill Book Company.

Mulvey, L. (1975). Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema, Screen,16, 3, pp. 6-18.

Mulvey, L. ( 2003) Stillness in the Moving Image: Ways of Visualizing Time and Its Passing, in Saving the Image: Art after Film. Manchester: Manchester Metropolitan University, pp. 78-89.

Nares, J. (2014) James Nares.New York: Rizzoli.

Newhall, B. (1937)Moving Pictures in Photography: A Short Critical History. New York: The Museum of Modern Art,p. 88-90.

Niedich, W. (2003) Blow-Up: Photography, Cinema and the Brain. Riverside California: Distributed Art Publishers.

Parks, L. (2005) Cultures in Orbit: Sattelites and the Televisual.Durham: Duke University Press.

Parr, A. (2005) The Deleuze DictionaryEdinburgh: University Press, p175.

Penz, F. & Lu, A. (2011) Urban Cinematics.Bristol: Intellect.

Pile, S. (1999) The Body and the City: Psychoanalysis, Space and Subjectivity. London: Routledge.

Pile, S. (2005) Real Cities.London: Sage Publications Ltd.

Prakash, G. (2012) Noir Urbanisms: Dystopic Images of the Modern City. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Raban, J. (1974) Soft City.London: Picador.

Simmel, G. (1950) The Stranger, inThe Sociology of Georg Simmel, Cambridge: The Free Press.

Simmel, G. (1950) The Metropolis and Mental Life, inThe Sociology of Georg Simmel, Cambridge: The Free Press.

Sjöberg, P. (2011) I Am Here, or, The Art of Getting Lost: Patrick Keiller and the New City Symphony, in Penz, F. & Lu, A. (2011) Urban Cinematics. Bristol: Intellect.

Soja, E. W. (1996) Postmetroplois: Critical studies of cities and regions. Oxford: Blackwell.

Stezaker, J. (2008) Film Stills, Still: An email conversation between John Stezaker and David Campanyin John Stezaker Film Still. London: Ridinghouse.

The Difference Between Mystery & Suspense(1970) Alfred Hitchcock – American Film Institute [Online Video] Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-Xs111uH9ss[Accessed August 2015].

The History of Frame Rate for Film(2015) Filmmaker IQ [Online Video]. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mjYjFEp9Yx0 [Accessed August 2015].

UN (2007) World Urbanization Prospects – United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs Population Division.

Vitale, C. (2011) The time Image: Towards a Direct Imaging of Time to Crystal-Images.[Online] Available from: https://networkologies.wordpress.com/2011/04/29/tips-for-reading-deleuzes-cinema-ii-the-time-image-towards-a-direct-imaging-of-time/[Accessed August 2015].

Vertigo (1958) [Film] Directed by Alfred Hitchcock. USA: Paramount Pictures

Wall, J. (1996) Frames of Reference, Artforum (September), pp, 188-193.

Webber, A. (2008)Cities in Transition. London: Wallflower Press.

Wells, H. G. (1895) The Time Machine.UK: William Heinemann.

Wertheimer, M. (1912) Experimental Studies on Motion Vision, Zeitschrift für Psychologie,61(1): pp. 161-265.

Wollen, P. (1984) Fire and Ice, Photographies, 4.Paris, p.118-120.