Dutch photographer Bas Losekoot won our recent theme ‘An Instant’ with a stunning freeze-frame street moment. The image struck us, both for its arresting subject matter, and for its sublime technical execution, exhibiting a sharpness, or a ‘hyper-reality’ as Bas would put it, unusual for a street image.

Looking through the series from which that image was taken, the Urban Millennium Project, each frame tells a story of the urban world that now half of the world inhabits – how it confines us, and we retract into our inner-selves in public. How the busiest places can be the loneliest. Bas accentuates these feelings with his considered compositions, where negative space heightens the feelings of isolation and introspection, and where looming shadows are often more prominent than the people.

We sat down with Bas to ask him about his ideas behind the Urban Millennium Project, and his techniques for capturing them. His answers are insightful and thought-provoking.

Bas – congratulations on winning our fifth theme ‘An Instant’ with an image that was described by Olivia Arthur and the Life Framer editors as distinctive, full of energy and “a decisive moment of almost-interaction in our busy urban environments”. Can you tell us a little more about the image and the series it comes from ‘The Urban Millennium Project’?

In 2011 I started a project towards the beginning of the Urban Millennium; the historic turning point where more people now live in cities than in rural areas. For me this fact was the starting point for thinking about how this growing population density is influencing the inhabitants of the world’s megacities.

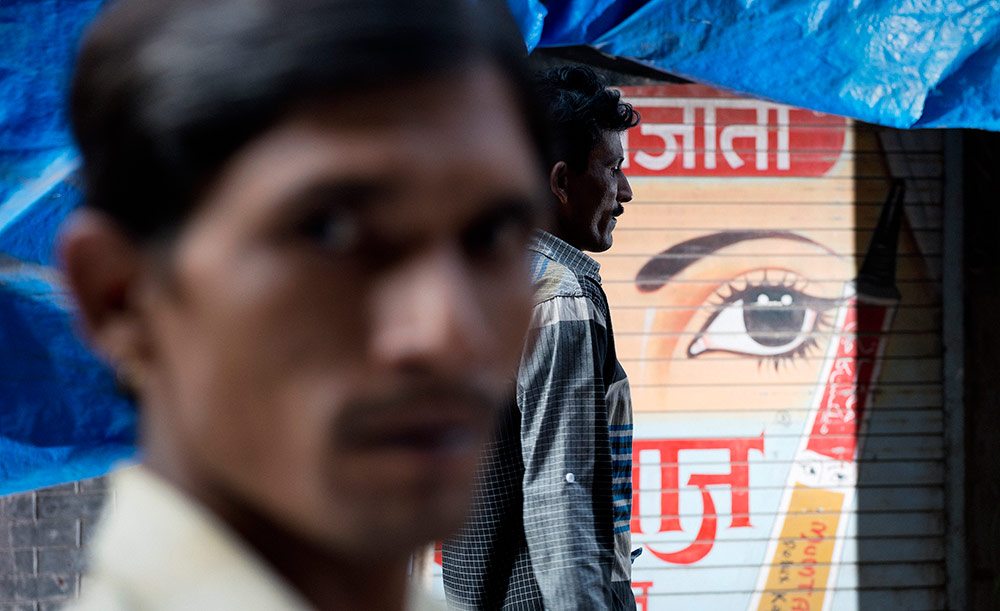

At the moment, we are facing the biggest wave of urbanization in human history. In this project, I try to imagine the consequences for everyday city-life in the future. I consider the city to be the centre of globalised society and with this project, I research how this reflects on its residents. What happens when too many people live on a small surface? How do people react to each other in areas of overpopulation? To me street life is a continuous stream of split-second meetings.

For this specific image, I positioned myself on a busy street corner close to Union Square, New York City, where I worked the entire afternoon. I like places where there is very little personal space. Frankly, I position myself on street corners in the hope people will literally bump into each other! This image is one of these ‘one-in-a-million’ shots where light, focus and timing turned out just perfect.

The Urban Millennium Project: New York

As a photographer I was initially trained in the studio. It was only later on that I got interested in urban photography, and I started to combine these genres and bring the lights to the streets. I began to imagine the city as a big studio and it citizens as actors. By approaching the street as a stage, it made me wonder if we might perform our lives. I started to read about performativity theory, for example by the sociologist Erving Goffman – about the presentation of self in everyday life. It seems, in daily life, we are performing social roles and we wear the appropriate mask for that. While commuting the city, we drop this mask and replace it for another one, the mask of ‘self-protection’. I am interested in this mask, because I believe it provides us a lot of information of the self and the construction of identity.

Next to the light I am drawn to the working of fast shutter speeds; the unique quality of photography to arrest movement. I try to capture offbeat moments that remain unseen at the everyday speed of life. Working with this apparatus I like the images to appear as film stills out of a non-linear urban continuum. I intend to slow people down and make them dwell on the meaning of inhabiting the new reality of fast growing cities.

“I began to imagine the city as a big studio and it citizens as actors. It seems, in daily life, we are performing social roles and we wear the appropriate mask for that. While commuting the city, we drop this mask and replace it for another one, the mask of ‘self-protection’”.

The core question when starting this project was; are we creating an ideal society by making these cities grow at such speed and to such sizes? I was reading many of Rem Koolhaas’s books where he talks about the ‘escape to the future’, and where cities can only exist by the virtue of their own problems. I got interested in how this fast growing urban density is influencing human behaviour. To understand modern urban life I started to approach the city as a confinement, not an urban jungle but more a human zoo. I would visit its cages.

Later on, I referred to my work more as a forest. The buildings are the trees; the roads are the rivers. The forest is also a symbol for the overdose of stimuli we have to cope with while manoeuvring in the streets. By instinct, every impulse is processed as a one-second judgement. The forest is dense, we feel at home there, but it is also full of danger, we always have to pay attention. Just like in the natural forest, it is a survival of the fittest. In this body of work, I am interested in the animals that live in the forest.

The Urban Millennium Project: Mumbai

In urban life, there is an interesting paradox at play; we dwell with the desire to belong to a group but we seem to avoid contact with that group. Engagement with strangers rarely happens because of the challenges and insecurities that come with it; we could get hurt or disappointed, or we might get involved in a long conversation that we do not have time for. We need the group but we like to be an individual as well. Therefore, often the stranger remains unknown and we are left being alone together.

Next to that, I believe that the overstimulation of modern city life makes us detach from space and reality. In a sense, we all get increasingly alienated from social interaction in the streets. While commuting, we always have used many tools for avoidance practice, like eating, reading or sleeping. Nowadays we can email, text, skype, play games, watch films, shoot photos, edit, publish and send them etc. Through the use of the Smartphone, we’ve brought the office into the street. The most performed act is the one of pretending to be busy. We have many screens to hide ourselves with, like sunglasses, earplugs and telephones. Whenever we are in an uncomfortable environment, we grab these devices, dramatically decreasing the chance of interacting with individuals outside of our social group.

I have an intrinsic desire to understand people better. With the use of the camera, I hope to get closer and understand them a bit more. I try to get into peoples’ minds and imagine their lives and dreams. I like my photography to create experiences rather then tell stories.

The speed of urban life is so intense that I never have the time to talk to people when they pass by. Next to that, I don’t like my presence as a photographer to influence the subject. You can see it in people’s eyes when they are aware being watched. After installing the lights, as soon I look into the viewfinder I become a fly on the wall. Sometimes I even forget that I am there. It is a disembodiment, or like Garry Winogrand has put it: the closest you can get to non-existence. This for me personally results in many accidents in traffic while photographing!

“I believe that the over-stimulation of modern city life makes us detach from space and reality. In a sense, we all get increasingly alienated from social interaction in the streets”.

I cannot deny that I reflect the loneliness of photographing alone in the street, on the people I capture. I photograph the isolated, uncanny and even alienated people because I feel amazingly close to them. In fact, I am like them, I mean I can see myself navigating through urban space, stressed by the pressure of everyday life, like that as well. Loneliness in cities is counter-intuitive mental disease number one. I never really understood how the walls of our apartments we live in can really make people isolated. There is another cosmos behind this ten centimetres, which we often never get to know.

With this project, I like to plea for a more open and communicating ambience on the streets where we dwell every day. The encounter with the stranger might be an interesting opportunity or exciting friendship. To share experiences in real life rather than online, we can transform the street into a more human environment, where people look at each other rather than at their telephones. A small gesture to the stranger can mean a lot to him or her. I believe it is in these small urban encounters, where we are triggered by curiosity and can overcome our fear for the unknown; whether the stranger is the casual passer-by on the street, your neighbour or a refugee.

You gained your BA Photography in 2001 and then returned to university in 2014 for your MA Photography. What role has university played in your practice? And what are the most important things it taught you?

My BA in photography was a good experience, where I graduated with a film that combined media like video, super8, freeze frames and still 35 mm photography. Later I started studying for DOP at the film academy in Amsterdam, realizing I missed the intimacy of still photography. Coming back to photography, I got hungry for more sociological and urban theory and started the MA Photography and Urban Cultures at Goldsmiths, University of London. There I built a theoretical framework and crystallized my ideas and concepts. My fascination for the correlation of photography and cinema made me study the cinematic affect and experience.

The Urban Millennium Project: London

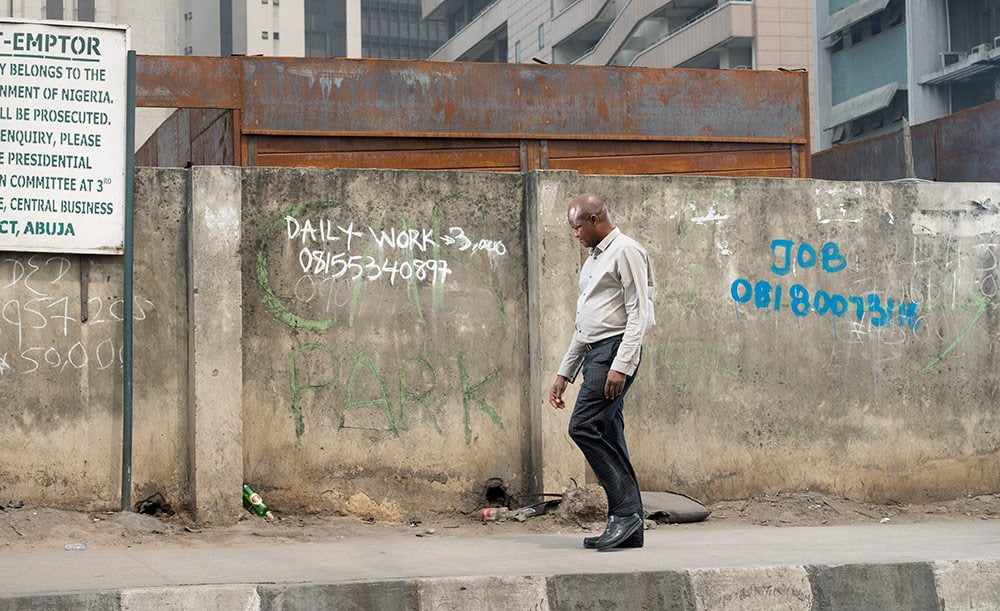

Until now I have worked in seven cities, I recently added London, Hong Kong and Lagos/Nigeria. This year I am about to finish the project in Istanbul and Mexico City. All cities are selected on the criteria of population density and level of commuting in its city centres. I like the cities to be some sort of zipper of the world; a meeting place of different cultures and tribes. I consider this diversity to be the spectacle of the street: the theatre of the real life. It is a pressure cooker for human expression and development. To me the high concentration and diversity of strangers represent the fun and excitement of exploring the unknown. I am convinced the street is a place to learn from; it can hold up a mirror to society.

When starting this project I was interested in the differences of all the people I photographed on the streets. However, the differences I experienced were quite obvious. I wanted the project to go beyond that and emphasize the similarities. Due to globalisation, the centres of megacities, including its citizens, get visually amazingly homogeneous. Around the world, we see generations wearing the same clothing, listening to the same music and watching the same movies. In the end, genetically we belong to the same group of primates – something I find very reassuring. Nowadays I am more interested in the things we have in common.

Do you have a (or some) favourite image(s) so far? What is it about this/these one(s)?

I have seen my project evolving through the years, from a more architecture to more sociological approach. Each successive city demands a next level methodology. Since New York where I worked on the blueprint of this project, I now know what I am looking for. I prepare my travels carefully, work at least one month in each city, study the movement on the street, mind-mapping the city. Nevertheless, I always believe there is the unexpected around the corner, so I have to work with an intuitive eye. Like Alex Webb when referring to Cartier-Bresson – he described how, when working in the street, you can smell the possibility of a picture.

One example of this is the image shot in Lagos Nigeria (below), where I was working for a month this February. (The work is, as we speak, on show in BOZAR, Centre for Fine Arts in Brussels) Lagos forced me really to re-think my methods. You cannot go out and just shoot wherever you like, so you had to get creative in finding interesting locations to work. Sometimes unexpected elements can get juxtaposed in an extraordinary mise en scène.

I love street photography in all its forms. I try to learn from its rich history and find a new angle to it. I admire the black and white masters like Robert Frank, Ray Metzker and Garry Winogrand. As well as the later colour specialists like Alex Webb, Joel Meyerowitz and Saul Leiter. I am also drawn to more conceptual approaches of photographers that use the street more as a space rather than place, like Beat Streuli, Paul Graham and Jeff Wall.

Last week I attended a screening of the film Koyaanisqatsi with live performance of Philip Glass and his ensemble. This film is street photography to me as well and it touches upon the modern city life experience in such an extraordinary way; an amazing experience.

The Urban Millennium Project: Lagos

“Study the rich history of art and photography, twist it one degree and make it your own”.

I always considered curiosity to be the motor of my work (and for life in general as well). To younger photographers I would like to give the following advice: Study the rich history of art and photography, twist it one degree and make it your own.

At the moment, I am working with the great designer Teun van der Heijden on a book that will be released next year. The project-website will soon be completed including a new design at a new URL. My dream is to show the work in all the cities where I have worked. Together with an architect, I am developing an exhibition, based on the concept of the Panopticon. It will be a cinematic experience in a circular installation of light boxes in which you can go inside as well as walk around, like an imaginary trip around the world. Light boxes emphasize the backlight I use in my photographs. The circular shape of the installation connects to issues of gaze, power and infinity. It will be a multilayered demonstration of private lives in public places.

The Urban Millennium Project: Sao Paulo