Author: Bas Losekoot

YIP Art – Auction

On Saturday 7 October 2017 the biennial YiPArt Photo auction took place for the eighth time in Paradiso Noord. In total, the auction raised € 92,540!

The auction

Auctioneer Jop Ubbens effortlessly turned the concert hall into an exciting auction room. The giant portrait of 3 by 2 meters from Queen Máxima, photographed by Koos Breukel, was the most expensive work of the day, followed by Kingi Indigenous & Kingi Krant by Patricia Steur.

15 years YiP

After the auction, the 15th anniversary of Young in Prison took place. Visitors could visit a retrospective of 15 years of Young in Prison, follow workshops and enjoy the performances of various bands.

Creativity liberates!

Creativity is not a goal for Young in Prison, but a means for young people to get closer to themselves and discover their talents. Over the past 15 years YiP has worked in six different countries and with its creative programs helped thousands of (ex-) detained young people.

Life Framer – Interview

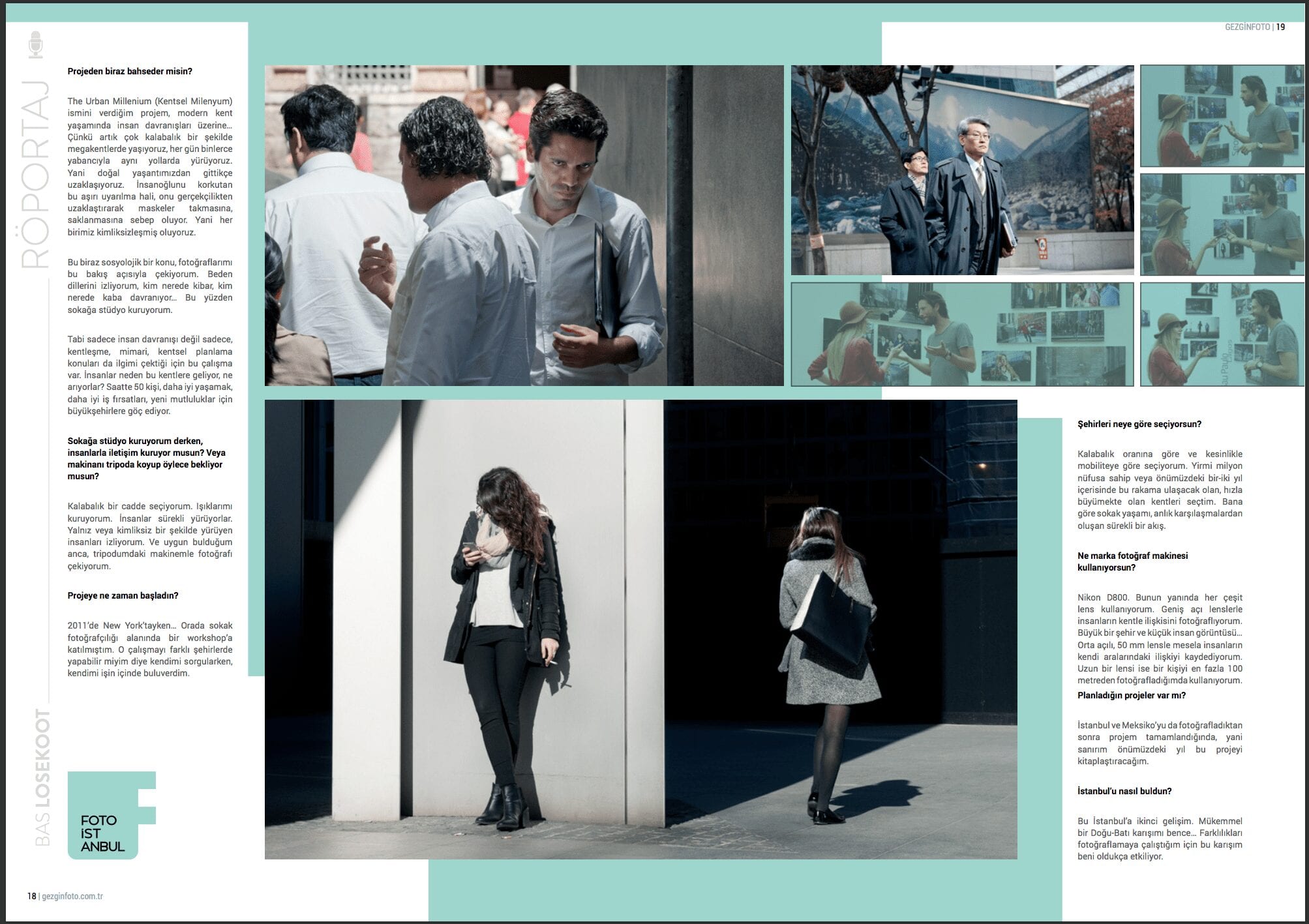

Dutch photographer Bas Losekoot won our recent theme ‘An Instant’ with a stunning freeze-frame street moment. The image struck us, both for its arresting subject matter, and for its sublime technical execution, exhibiting a sharpness, or a ‘hyper-reality’ as Bas would put it, unusual for a street image.

Looking through the series from which that image was taken, the Urban Millennium Project, each frame tells a story of the urban world that now half of the world inhabits – how it confines us, and we retract into our inner-selves in public. How the busiest places can be the loneliest. Bas accentuates these feelings with his considered compositions, where negative space heightens the feelings of isolation and introspection, and where looming shadows are often more prominent than the people.

We sat down with Bas to ask him about his ideas behind the Urban Millennium Project, and his techniques for capturing them. His answers are insightful and thought-provoking.

Bas – congratulations on winning our fifth theme ‘An Instant’ with an image that was described by Olivia Arthur and the Life Framer editors as distinctive, full of energy and “a decisive moment of almost-interaction in our busy urban environments”. Can you tell us a little more about the image and the series it comes from ‘The Urban Millennium Project’?

In 2011 I started a project towards the beginning of the Urban Millennium; the historic turning point where more people now live in cities than in rural areas. For me this fact was the starting point for thinking about how this growing population density is influencing the inhabitants of the world’s megacities.

At the moment, we are facing the biggest wave of urbanization in human history. In this project, I try to imagine the consequences for everyday city-life in the future. I consider the city to be the centre of globalised society and with this project, I research how this reflects on its residents. What happens when too many people live on a small surface? How do people react to each other in areas of overpopulation? To me street life is a continuous stream of split-second meetings.

For this specific image, I positioned myself on a busy street corner close to Union Square, New York City, where I worked the entire afternoon. I like places where there is very little personal space. Frankly, I position myself on street corners in the hope people will literally bump into each other! This image is one of these ‘one-in-a-million’ shots where light, focus and timing turned out just perfect.

The Urban Millennium Project: New York

As a photographer I was initially trained in the studio. It was only later on that I got interested in urban photography, and I started to combine these genres and bring the lights to the streets. I began to imagine the city as a big studio and it citizens as actors. By approaching the street as a stage, it made me wonder if we might perform our lives. I started to read about performativity theory, for example by the sociologist Erving Goffman – about the presentation of self in everyday life. It seems, in daily life, we are performing social roles and we wear the appropriate mask for that. While commuting the city, we drop this mask and replace it for another one, the mask of ‘self-protection’. I am interested in this mask, because I believe it provides us a lot of information of the self and the construction of identity.

Next to the light I am drawn to the working of fast shutter speeds; the unique quality of photography to arrest movement. I try to capture offbeat moments that remain unseen at the everyday speed of life. Working with this apparatus I like the images to appear as film stills out of a non-linear urban continuum. I intend to slow people down and make them dwell on the meaning of inhabiting the new reality of fast growing cities.

“I began to imagine the city as a big studio and it citizens as actors. It seems, in daily life, we are performing social roles and we wear the appropriate mask for that. While commuting the city, we drop this mask and replace it for another one, the mask of ‘self-protection’”.

The core question when starting this project was; are we creating an ideal society by making these cities grow at such speed and to such sizes? I was reading many of Rem Koolhaas’s books where he talks about the ‘escape to the future’, and where cities can only exist by the virtue of their own problems. I got interested in how this fast growing urban density is influencing human behaviour. To understand modern urban life I started to approach the city as a confinement, not an urban jungle but more a human zoo. I would visit its cages.

Later on, I referred to my work more as a forest. The buildings are the trees; the roads are the rivers. The forest is also a symbol for the overdose of stimuli we have to cope with while manoeuvring in the streets. By instinct, every impulse is processed as a one-second judgement. The forest is dense, we feel at home there, but it is also full of danger, we always have to pay attention. Just like in the natural forest, it is a survival of the fittest. In this body of work, I am interested in the animals that live in the forest.

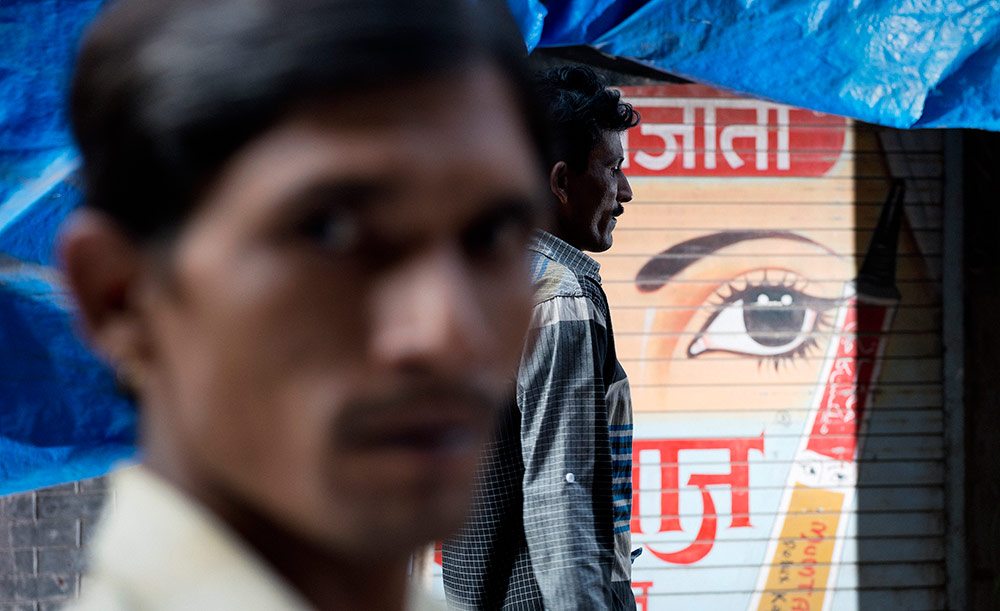

The Urban Millennium Project: Mumbai

In urban life, there is an interesting paradox at play; we dwell with the desire to belong to a group but we seem to avoid contact with that group. Engagement with strangers rarely happens because of the challenges and insecurities that come with it; we could get hurt or disappointed, or we might get involved in a long conversation that we do not have time for. We need the group but we like to be an individual as well. Therefore, often the stranger remains unknown and we are left being alone together.

Next to that, I believe that the overstimulation of modern city life makes us detach from space and reality. In a sense, we all get increasingly alienated from social interaction in the streets. While commuting, we always have used many tools for avoidance practice, like eating, reading or sleeping. Nowadays we can email, text, skype, play games, watch films, shoot photos, edit, publish and send them etc. Through the use of the Smartphone, we’ve brought the office into the street. The most performed act is the one of pretending to be busy. We have many screens to hide ourselves with, like sunglasses, earplugs and telephones. Whenever we are in an uncomfortable environment, we grab these devices, dramatically decreasing the chance of interacting with individuals outside of our social group.

I have an intrinsic desire to understand people better. With the use of the camera, I hope to get closer and understand them a bit more. I try to get into peoples’ minds and imagine their lives and dreams. I like my photography to create experiences rather then tell stories.

The speed of urban life is so intense that I never have the time to talk to people when they pass by. Next to that, I don’t like my presence as a photographer to influence the subject. You can see it in people’s eyes when they are aware being watched. After installing the lights, as soon I look into the viewfinder I become a fly on the wall. Sometimes I even forget that I am there. It is a disembodiment, or like Garry Winogrand has put it: the closest you can get to non-existence. This for me personally results in many accidents in traffic while photographing!

“I believe that the over-stimulation of modern city life makes us detach from space and reality. In a sense, we all get increasingly alienated from social interaction in the streets”.

I cannot deny that I reflect the loneliness of photographing alone in the street, on the people I capture. I photograph the isolated, uncanny and even alienated people because I feel amazingly close to them. In fact, I am like them, I mean I can see myself navigating through urban space, stressed by the pressure of everyday life, like that as well. Loneliness in cities is counter-intuitive mental disease number one. I never really understood how the walls of our apartments we live in can really make people isolated. There is another cosmos behind this ten centimetres, which we often never get to know.

With this project, I like to plea for a more open and communicating ambience on the streets where we dwell every day. The encounter with the stranger might be an interesting opportunity or exciting friendship. To share experiences in real life rather than online, we can transform the street into a more human environment, where people look at each other rather than at their telephones. A small gesture to the stranger can mean a lot to him or her. I believe it is in these small urban encounters, where we are triggered by curiosity and can overcome our fear for the unknown; whether the stranger is the casual passer-by on the street, your neighbour or a refugee.

You gained your BA Photography in 2001 and then returned to university in 2014 for your MA Photography. What role has university played in your practice? And what are the most important things it taught you?

My BA in photography was a good experience, where I graduated with a film that combined media like video, super8, freeze frames and still 35 mm photography. Later I started studying for DOP at the film academy in Amsterdam, realizing I missed the intimacy of still photography. Coming back to photography, I got hungry for more sociological and urban theory and started the MA Photography and Urban Cultures at Goldsmiths, University of London. There I built a theoretical framework and crystallized my ideas and concepts. My fascination for the correlation of photography and cinema made me study the cinematic affect and experience.

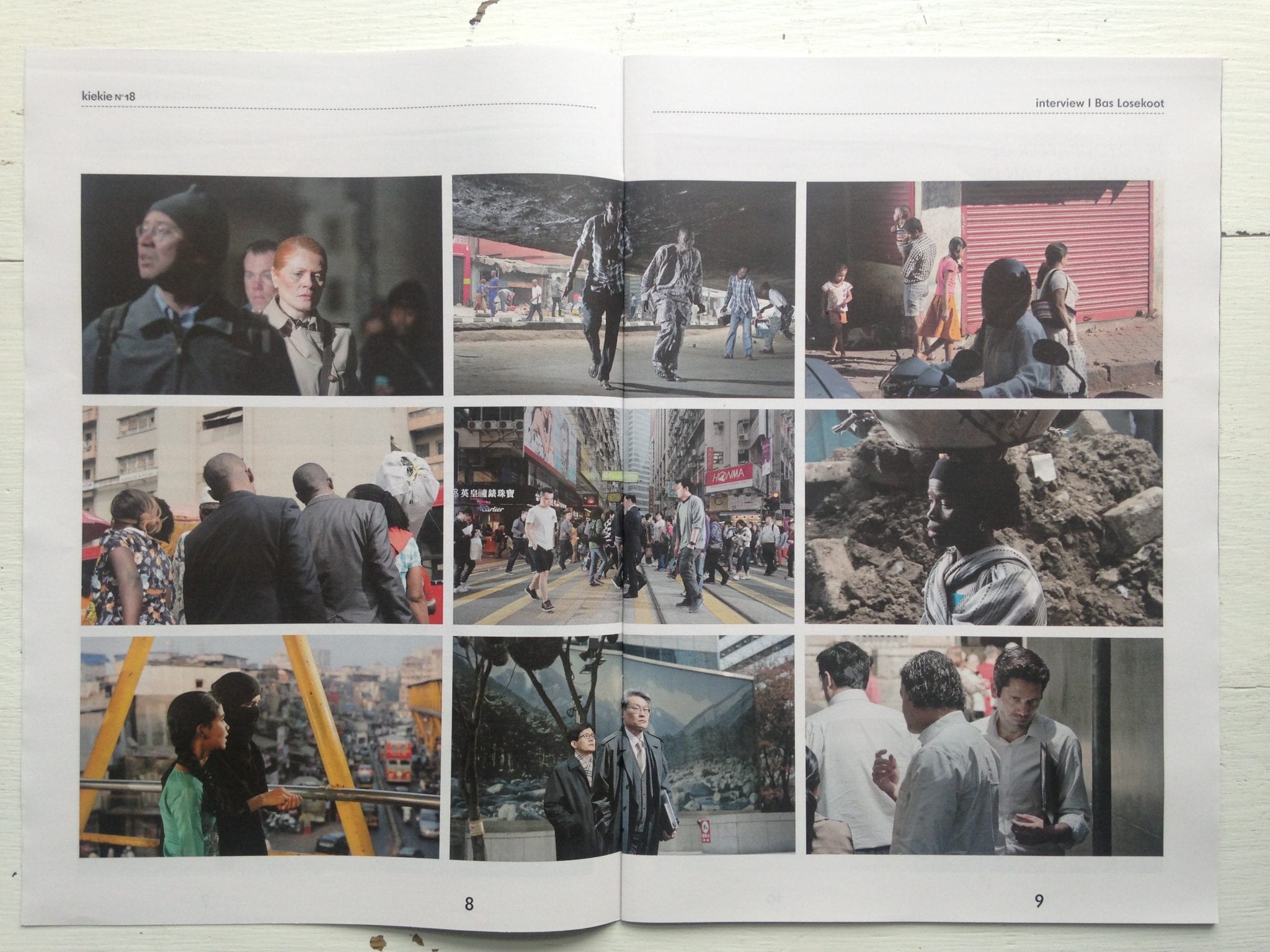

The Urban Millennium Project: London

Until now I have worked in seven cities, I recently added London, Hong Kong and Lagos/Nigeria. This year I am about to finish the project in Istanbul and Mexico City. All cities are selected on the criteria of population density and level of commuting in its city centres. I like the cities to be some sort of zipper of the world; a meeting place of different cultures and tribes. I consider this diversity to be the spectacle of the street: the theatre of the real life. It is a pressure cooker for human expression and development. To me the high concentration and diversity of strangers represent the fun and excitement of exploring the unknown. I am convinced the street is a place to learn from; it can hold up a mirror to society.

When starting this project I was interested in the differences of all the people I photographed on the streets. However, the differences I experienced were quite obvious. I wanted the project to go beyond that and emphasize the similarities. Due to globalisation, the centres of megacities, including its citizens, get visually amazingly homogeneous. Around the world, we see generations wearing the same clothing, listening to the same music and watching the same movies. In the end, genetically we belong to the same group of primates – something I find very reassuring. Nowadays I am more interested in the things we have in common.

Do you have a (or some) favourite image(s) so far? What is it about this/these one(s)?

I have seen my project evolving through the years, from a more architecture to more sociological approach. Each successive city demands a next level methodology. Since New York where I worked on the blueprint of this project, I now know what I am looking for. I prepare my travels carefully, work at least one month in each city, study the movement on the street, mind-mapping the city. Nevertheless, I always believe there is the unexpected around the corner, so I have to work with an intuitive eye. Like Alex Webb when referring to Cartier-Bresson – he described how, when working in the street, you can smell the possibility of a picture.

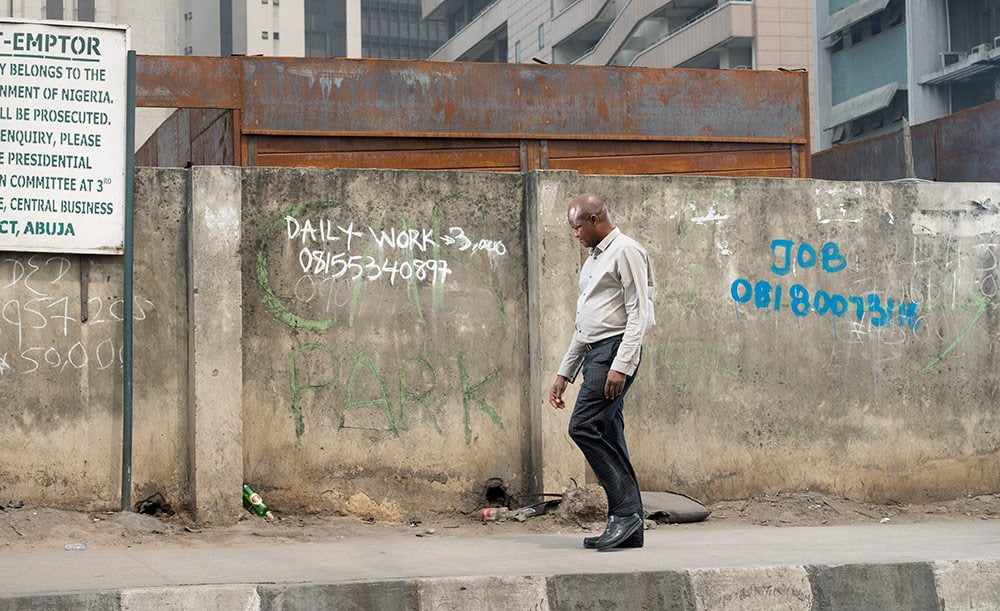

One example of this is the image shot in Lagos Nigeria (below), where I was working for a month this February. (The work is, as we speak, on show in BOZAR, Centre for Fine Arts in Brussels) Lagos forced me really to re-think my methods. You cannot go out and just shoot wherever you like, so you had to get creative in finding interesting locations to work. Sometimes unexpected elements can get juxtaposed in an extraordinary mise en scène.

I love street photography in all its forms. I try to learn from its rich history and find a new angle to it. I admire the black and white masters like Robert Frank, Ray Metzker and Garry Winogrand. As well as the later colour specialists like Alex Webb, Joel Meyerowitz and Saul Leiter. I am also drawn to more conceptual approaches of photographers that use the street more as a space rather than place, like Beat Streuli, Paul Graham and Jeff Wall.

Last week I attended a screening of the film Koyaanisqatsi with live performance of Philip Glass and his ensemble. This film is street photography to me as well and it touches upon the modern city life experience in such an extraordinary way; an amazing experience.

The Urban Millennium Project: Lagos

“Study the rich history of art and photography, twist it one degree and make it your own”.

I always considered curiosity to be the motor of my work (and for life in general as well). To younger photographers I would like to give the following advice: Study the rich history of art and photography, twist it one degree and make it your own.

At the moment, I am working with the great designer Teun van der Heijden on a book that will be released next year. The project-website will soon be completed including a new design at a new URL. My dream is to show the work in all the cities where I have worked. Together with an architect, I am developing an exhibition, based on the concept of the Panopticon. It will be a cinematic experience in a circular installation of light boxes in which you can go inside as well as walk around, like an imaginary trip around the world. Light boxes emphasize the backlight I use in my photographs. The circular shape of the installation connects to issues of gaze, power and infinity. It will be a multilayered demonstration of private lives in public places.

The Urban Millennium Project: Sao Paulo

Kiekie Tabloid – Interview

Interview met Denise Woerdman

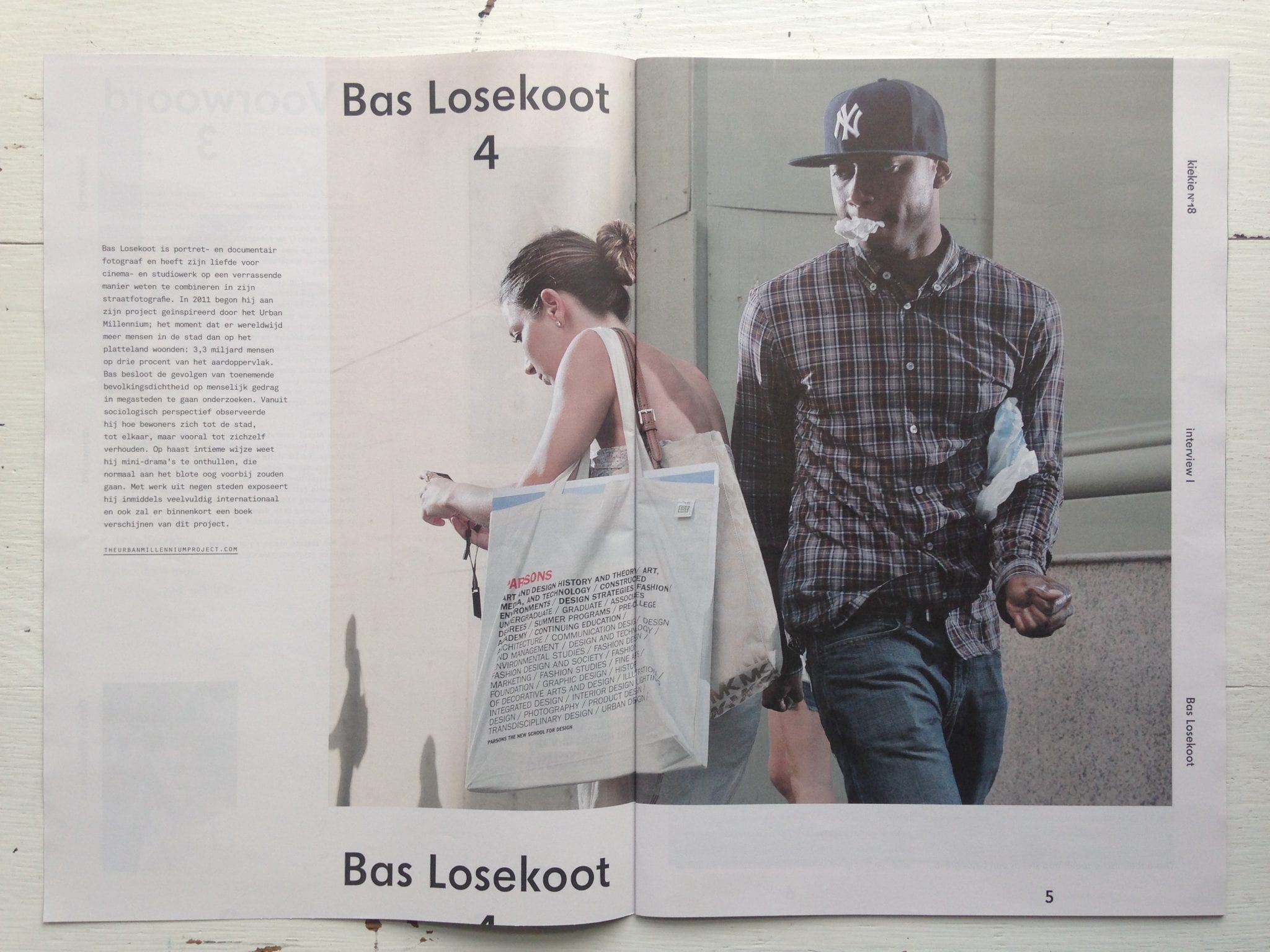

Bas Losekoot is portret- en documentair fotograaf en heeft zijn liefde voor cinema- en studiowerk op een verrassende manier weten te combineren in zijn straatfotografie. In 2011 begon hij aan zijn project geïnspireerd door het Urban Millennium; het moment dat er wereldwijd meer mensen in de stad dan op het platteland woonden: 3,3 miljard mensen op drie procent van het aardoppervlak. Bas besloot de gevolgen van toenemende bevolkingsdichtheid op menselijk gedrag in megasteden te gaan onderzoeken. Vanuit sociologisch perspectief observeerde hij hoe bewoners zich tot de stad, tot elkaar, maar vooral tot zichzelf verhouden. Op haast intieme wijze weet hij mini-drama’s te onthullen, die normaal aan het blote oog voorbij zouden gaan. Met werk uit negen steden exposeert hij inmiddels veelvuldig internationaal en ook zal er binnenkort een boek verschijnen van dit project.

Je bent in 2001 afgestudeerd aan de KABK, waar ging je eindexamenproject over?

”Ik was al vroeg geïnteresseerd in bewegend beeld en ben afgestudeerd met een film. De grote thema’s in dit project waren criminaliteit en obsessie. De film ging over een ex-gedetineerde, die lang heeft vastgezeten. Ik ben hem gaan volgen en samen hebben we plekken bezocht die belangrijk waren in zijn leven. Ik heb deze vervolgens gefilmd en gefotografeerd en heb ook geluid opgenomen; een echte multimedia dus. Dat was in die tijd “not done” op mijn opleiding: Film en fotografie waren aparte vakgebieden en het werd niet gewaardeerd dat ik hiermee ging experimenteren voor het eindexamenproject. Opmerkelijk als je bedenkt dat tegenwoordig op veel fotoacademies, film een verplicht vak is.

Na mijn afstuderen ben ik verschillende filmproductiebedrijven in Amsterdam gaan aanschrijven en werd zodoende gekoppeld aan de zeer bijzondere cameraman: Bert Pot. Van hem heb ik ontzettend veel geleerd en dat motiveerde mij om naar de Filmacademie te gaan. Ik heb dat slechts een jaar gedaan, want ik verlangde terug naar de vrijheid die bij fotografie hoorde. Maar de visuele vertelvorm van cinema, heeft mij altijd zeer aangesproken. Mijn recente Urban Millennium Project is er sterk door beïnvloed. Niet alleen door gebruik van licht, maar ook kadrering, timing, mise-en-scène en kleurcorrectie. Foto essays edit ik aan de hand van film montage technieken.”

Dus dat filmische is altijd nog aanwezig in je fotografie?

”Ja, ik vind cinema nog steeds ontzettend inspirerend. Ik heb vroeger veel gewerkt als stills-fotograaf en dat doe ik nu soms ook nog wel eens. Vorig jaar heb ik een Master gevolgd in Londen, Photography in Urban Cultures, en ik daar schreef ik mijn dissertatie over the “cinematic”, over wat het cinematografische nu precies is. Een stilstaand beeld uit een film vind ik vaak fascinerend, als ik een film kijk zet ik het beeld vaak stil en maak ik daar een screenshot van. Het is lastig om dit project een kader te geven. Is het documentaire fotografie of toch fictie? Is het geënsceneerd of niet? Het is het spanningsveld tussen feit en fictie dat ik interessant vind. In mijn recente project wil ik het van beide kanten onderzoeken.”

Wanneer besloot je om met het Urban Millennium project te beginnen?

”Mijn interesse heeft altijd gelegen bij socio-culturele onderwerpen. De laatste jaren raakte ik ook geïnteresseerd in architectuur en stedelijke theorie. In 2007 brak de dag aan dat er meer dan helft van de wereldbevolking in steden woonde, ten opzichte van het platte land. Dit zette mij aan het denken over wat het is dat mensen beweegt om naar de stad te trekken. Hoe komt het dat we in steden willen wonen die alsmaar drukker worden? Lagos bijvoorbeeld, groeit met 57 mensen per uur. Waar komen die de stad binnen en waar blijven ze? Wat is de belofte van de stad? Ik ben de gevolgen van overbevolking in de drukste steden ter wereld gaan fotograferen met een sociologische aanpak. Ik ben bijvoorbeeld benieuwd naar wanneer we het gevoel hebben dat we “samen” zijn. Ik let op hoe we onszelf presenteren op straat; wat laten we zien en wat verbergen we? Dragen we misschien een soort masker? Hoe kunnen we bepaalde handgebaren en oogopslagen lezen?

De momenten waarop ik fotografeer zijn altijd de drukste momenten van de dag, vaak tijdens ochtend- en avondspits. Ik fotografeer op de knelpunten van de stad, die voor mij symbool staan voor de knelpunten in de menselijke psyche. De eerste stad die ik fotografeerde was New York, omdat ik daar was voor een workshop van Alex Webb. Ik ontwikkelde daar een blauwdruk die ik zou kunnen toepassen op andere steden. Ik maakte een wishlist van 9 steden verspreid over alle continenten gebaseerd op de mate van bevolkingsdichtheid en mobiliteit; de beweging van voetgangers met name woon-werk verkeer.”

Gezichtsuitdrukkingen en handgebaren worden hierdoor verheven tot dramatische gebeurtenissen

Je flitst je onderwerpen hard in, waarom ben je dat op die manier gaan doen en met welke reden?

”Deze techniek is gebaseerd op de dubbele licht situaties die ik ontdekte door de spiegelende gebouwen in het financiele district in Manhattan. Ik maakte daar veel gebruik van en ging ze missen op bewolkte dagen. Ik kwam toen op het idee om deze situaties zelf te gaan creëren. Ik ben jarenlang getraind in de studio en op filmsets en het leek mij interessant om met deze technieken te gaan experimenteren op straat. Fotografie heeft door sluitertijd de mogelijkheid beweging te bevriezen en het gebruik van flitsers versterken dat nog eens. Bovendien krijgen de beelden een film-still achtige kwaliteit waardoor je als kijker niet precies weet waar je naar aan het kijken bent. Gezichtsuitdrukkingen en handgebaren worden hierdoor verheven tot dramatische gebeurtenissen. Het nadeel was natuurlijk dat ik vanaf dat moment altijd door de stad struinde met zware statieven, flitsers, en zenders, haha. Ik heb in elke stad minimaal een maand, elke dag op straat gefotografeerd.”

Door welke fotografen ben je geïnspireerd ?

”Ik ben beïnvloed door vele soorten (stads) fotografie, bv het zwart/wit werk uit Chicago van Ray Metzker en Harry Gallahan, later de New York School zoals Alex Webb, Garry Winogrand en Joel Meyerowitz. Ik voel me ook aangetrokken tot conceptuelere aanpaken van bv. Jeff Wall, Beat Streuli en Paul Graham. Deze gebruiken de stad net als ik meer podium dan als onderwerp, meer als “space” dan “place”.”

Reageerden er ook weleens mensen boos als je ze fotografeerde op straat?

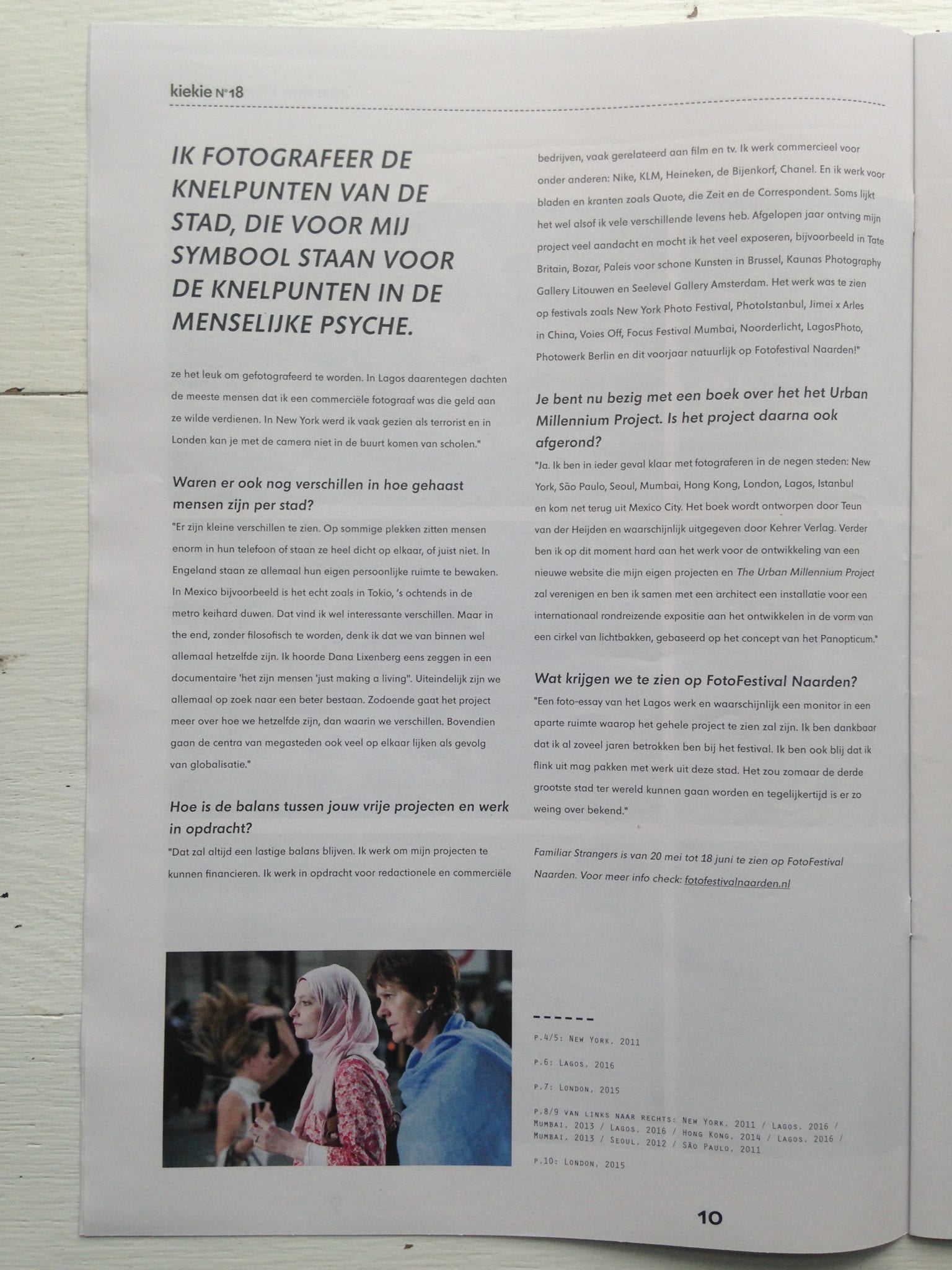

”Ik krijg naar verhouding weinig reacties. Ook als ik mensen van dichtbij sta te flitsen. Natuurlijk heb ik ook genoeg vervelende ervaringen maar dan vooral met beveiligingsagenten en politie. Dat ik het überhaupt overleefd heb. Ik ben naar steden geweest met behoorlijk gevaarlijke wijken. Wijken waar je echt de codes van de straat moet kennen. Ik ben een paar keer opgepakt en in vreemde busjes geduwd. Soms probeert er iemand een flitser te jatten. In reacties van mensen waren veel verschillen per stad. Zo waren de mensen in Mumbai over het algemeen super geïnteresseerd en vrolijk en vinden ze het leuk om gefotografeerd te worden. In Lagos daarentegen dachten de meeste mensen dat ik een commerciële fotograaf was die geld aan ze wilde verdienen. In New York werd ik vaak gezien als terrorist en London kan je met de camera niet in de buurt komen van scholen.”

Waren er ook nog verschillen in gehaastheid tussen de steden?

”Er zijn kleine verschillen te zien. Op sommige plekken zitten mensen enorm in hun telefoon. En op sommige plekken kunnen mensen heel relaxed dicht op elkaar staan en op andere plekken weer juist niet. In Engeland staan ze allemaal hun eigen persoonlijke ruimte te bewaken. In Mexico is het echt zoals in Tokio, ’s ochtends in de metro is het keihard duwen. Dat vind ik wel interessante verschillen. Maar in the end, zonder filosofisch te worden, denk ik dat we van binnen wel allemaal hetzelfde zijn. Ik hoorde Dana Lixenberg eens zeggen in een documentaire ‘het zijn mensen ‘just making a living’. Uiteindelijk zijn we allemaal op zoek naar een beter bestaan. Zodoende gaat het project ook veel meer over hoe wel hetzelfde zijn dan waarin we verschillen. Bovendien gaan de centra van megasteden ook veel op elkaar lijken als gevolg van globalisatie.”

Ik werk in opdracht om mijn projecten te kunnen financieren

Hoe is de balans tussen jouw vrije projecten en werk in opdracht?

”Dat zal altijd een lastige balans blijven. Ik werk in opdracht om mijn projecten te kunnen financieren. Ik werk in opdracht voor redactionele en commerciele bedrijven, vaak gerelateerd aan film en tv. Ik werk commercieel voor oa: Nike, KLM, Heineken, de Bijenkorf, Chanel. En ik werk voor bladen en kranten zoals Quote, die Zeit en de Correspondent. Soms lijkt het wel alsof ik vele verschillende levens heb.

Afgelopen jaar ontving mijn project veel aandacht en mocht ik het veel exposeren, bv in Tate Britain, Bozar, Paleis voor schone Kunsten in Brussel, Kaunas Photography Gallery Litouwen en Seelevel Gallery Amsterdam. Het werk was te zien op festivals oa. New York Photo Festival, PhotoIstanbul, Jimei x Arles in China, Voies Off, Focus Festival Mumbai, Noorderlicht, LagosPhoto, Photowerk Berlin, en natuurlijk Naarden!”

Foto Magazin Edition – Portfolio Publication

Portfolio Published in XL Foto Magazin Edtion: Der Mensch in der Mega-City

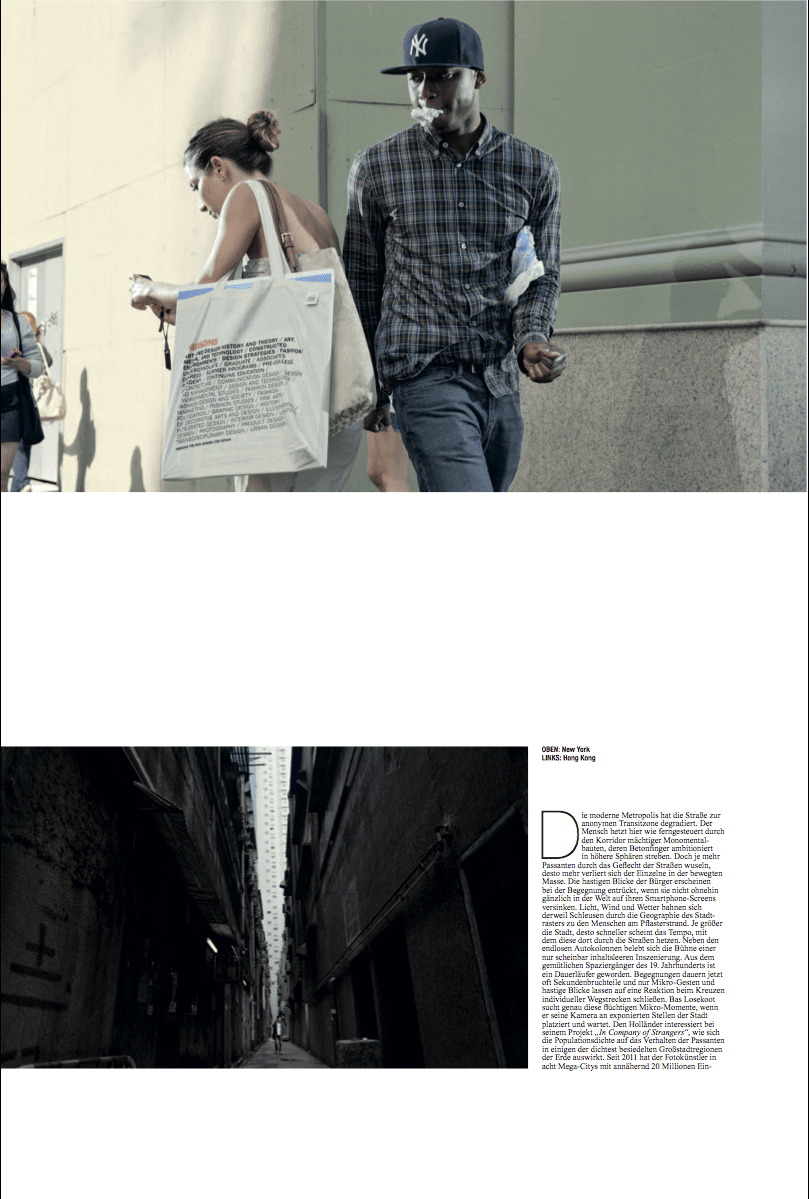

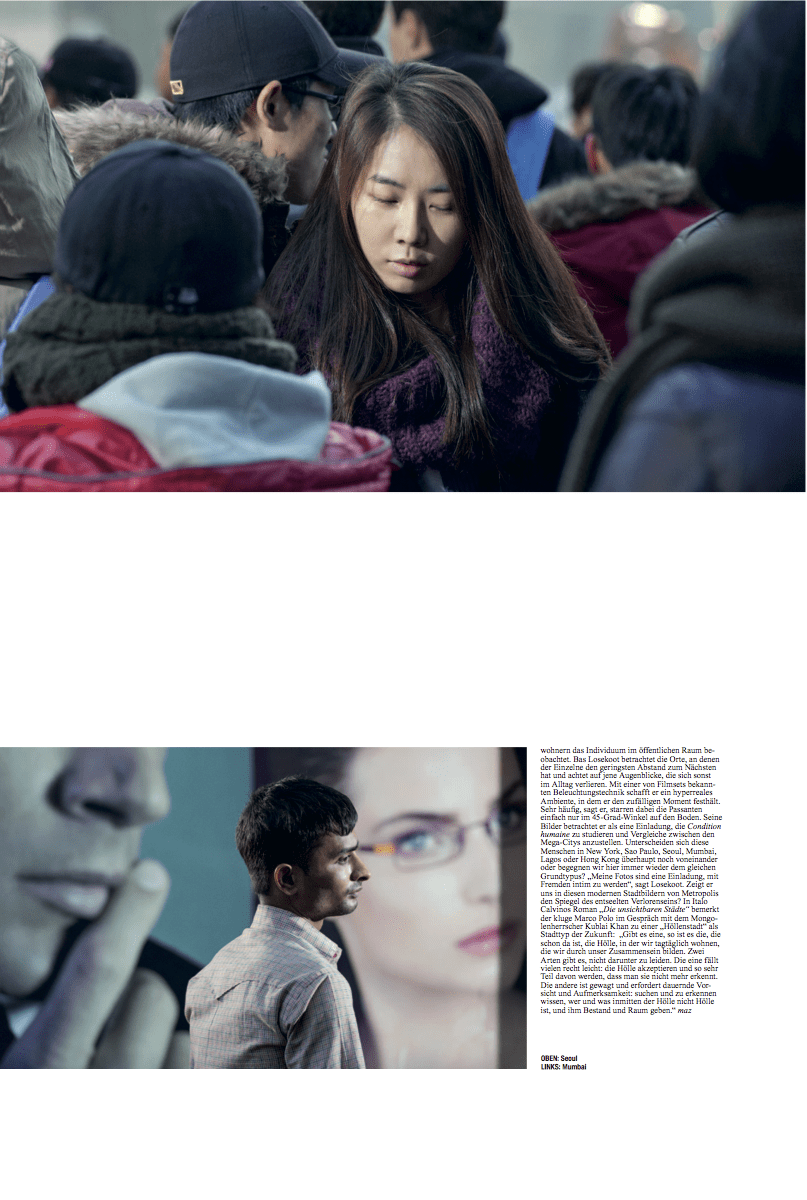

Die moderne Metropolis hat die Straße zur anonymen Transitzone degradiert. Der Mensch hetzt hier wie ferngesteuert durch den Korridor mächtiger Monomental- bauten, deren Betonfinger ambitioniert in höhere Sphären streben. Doch je mehr Passanten durch das Geflecht der Straßen wuseln, desto mehr verliert sich der Einzelne in der bewegten Masse. Die hastigen Blicke der Bürger erscheinen bei der Begegnung entrückt, wenn sie nicht ohnehin gänzlich in der Welt auf ihren Smartphone-Screens versinken. Licht, Wind und Wetter bahnen sich derweil Schleusen durch die Geographie des Stadt- rasters zu den Menschen am Pflasterstrand. Je größer die Stadt, desto schneller scheint das Tempo, mit dem diese dort durch die Straßen hetzen. Neben den endlosen Autokolonnen belebt sich die Bühne einer nur scheinbar inhaltsleeren Inszenierung. Aus dem gemütlichen Spaziergänger des 19. Jahrhunderts ist ein Dauerläufer geworden. Begegnungen dauern jetzt oft Sekundenbruchteile und nur Mikro-Gesten und hastige Blicke lassen auf eine Reaktion beim Kreuzen individueller Wegstrecken schließen. Bas Losekoot sucht genau diese flüchtigen Mikro-Momente, wenn er seine Kamera an exponierten Stellen der Stadt platziert und wartet. Den Holländer interessiert bei seinem Projekt „In Company of Strangers“, wie sich die Populationsdichte auf das Verhalten der Passanten in einigen der dichtest besiedelten Großstadtregionen der Erde auswirkt. Seit 2011 hat der Fotokünstler in acht Mega-Citys mit annähernd 20 Millionen Einwohnern das Individuum im öffentlichen Raum be- obachtet. Bas Losekoot betrachtet die Orte, an denen der Einzelne den geringsten Abstand zum Nächsten hat und achtet auf jene Augenblicke, die sich sonst im Alltag verlieren. Mit einer von Filmsets bekann- ten Beleuchtungstechnik schafft er ein hyperreales Ambiente, in dem er den zufälligen Moment festhält. Sehr häufig, sagt er, starren dabei die Passanten einfach nur im 45-Grad-Winkel auf den Boden. Seine Bilder betrachtet er als eine Einladung, die Condition humaine zu studieren und Vergleiche zwischen den Mega-Citys anzustellen. Unterscheiden sich diese Menschen in New York, Sao Paulo, Seoul, Mumbai, Lagos oder Hong Kong überhaupt noch voneinander oder begegnen wir hier immer wieder dem gleichen Grundtypus? „Meine Fotos sind eine Einladung, mit Fremden intim zu werden“, sagt Losekoot. Zeigt er uns in diesen modernen Stadtbildern von Metropolis den Spiegel des entseelten Verlorenseins? In Italo Calvinos Roman „Die unsichtbaren Städte“ bemerkt der kluge Marco Polo im Gespräch mit dem Mongo- lenherrscher Kublai Khan zu einer „Höllenstadt“ als Stadttyp der Zukunft: „Gibt es eine, so ist es die, die schon da ist, die Hölle, in der wir tagtäglich wohnen, die wir durch unser Zusammensein bilden. Zwei Arten gibt es, nicht darunter zu leiden. Die eine fällt vielen recht leicht: die Hölle akzeptieren und so sehr Teil davon werden, dass man sie nicht mehr erkennt. Die andere ist gewagt und erfordert dauernde Vor- sicht und Aufmerksamkeit: suchen und zu erkennen wissen, wer und was inmitten der Hölle nicht Hölle ist, und ihm Bestand und Raum geben.“ Manfred Zollner

PF Magazine – Interview by Naomi Heidinga

Interview in PF Magazine by Naomi Heidinga

Groepsdieren of miljoenen individuen in de stad?

Hoe houdt de mens zich staande in de steeds groter groeiende steden? Vinden we als groepsdieren de basis van ons geluk in de grote steden of zijn we er juist eenzamer? Deze paradox heeft Bas Losekoot onderzocht in zijn Urban Millennium Project. Hij bezocht negen megasteden op verschillende continenten om te onderzoeken hoe mensen op straat acteren. De straat vormt het decor, met de stadsmens als acteur. Door zijn manier van belichten springen kleine momenten eruit, momenten die anders aan ons voorbij zouden zijn gegaan.

In 2011 ging het project van Losekoot van start. Vanuit een interesse voor de steeds verder gaande urbanisatie. Geschat wordt dat in 2030 zo’n 60 procent van de wereldbevolking in grote steden woont. Het project is overduidelijk geïnspireerd door de stedelijke theorie, maar is uitgewerkt in sociologie. Waar in het begin meer de nadruk op de architectuur lag, zoomt hij later meer in op het individu in de stad. Zijn beelden laten, op een haast intieme wijze, privé situaties in het publieke domein zien.

Evolutie

“Ik vroeg me af welke invloed de bevolkingsdichtheid heeft op de manier hoe we met elkaar omgaan. Als je kijkt naar de evolutie van de mens, wonen we nog niet zo lang in grote steden. Aan dit leven zijn we nog steeds niet helemaal gewend. Bijna iedereen heeft in een bepaalde mate last van pleinvrees. Dit zie je terug in de manier waarop mensen zich presenteren in de publieke ruimte. Ondanks ons verlangen om bij een groep te horen, sluiten we ons in drukke ruimten vaak voor de ander af. We verschuilen ons achter een masker, met oordopjes, zonnebril en telefoon en een blasé houding. Ook zie je in drukke straten een natuurlijk spel, een soort krachtenmeting: wie gaat aan de kant voor wie. Heel interessant vind ik dat.”

Eenzaamheid

“Na het bezoeken van die negen steden ben ik er nog niet over uit. Helpt het leven in de stad ons bij het aangaan van sociale contacten of worden we juist eenzamer? Onlangs zag ik op AT5 een item over eenzaamheid onder Amsterdammers. Uit een onderzoek van de GGD blijkt 1 op de 8 Amsterdammers zich extreem eenzaam te voelen. Ook al wonen we dichtbij elkaar, toch weten we vaak niet wat zich aan de andere kant van onze 10 centimeter dikke muur afspeelt.”

Lichtspel

Losekoot bezocht vanaf 2011 New York, São Paulo, Seoul, Mumbai, Hong Kong, London, Istanbul, Lagos en Mexico Stad. “De eerste foto’s heb ik in New York in het financial district gemaakt. Daarna ben ik gaan fotografen in steden op bijna alle continenten. De keuze voor de verschillende steden werd op de eerste plaats ingegeven door de bevolkingsdichtheid. Daarnaast gold de mate van mobiliteit, de dynamiek van voetgangers in het centrum van die steden, of ik aan de slag kon met mijn werkwijze. In het financial district in New York heb je veel smalle straten met gebouwen met spiegelende gevels. Dat levert een interessant lichtspel op. Door de spiegeling in de ramen van omringde kantoorgebouwen ontstaat een dubbel-licht situatie. Dit effect heb ik nagebootst in andere foto’s door gebruik te maken van artificieel licht. Het gebruik van flitsers benadrukt de capaciteit waarover fotografie beschikt: een moment te bevriezen. Zo worden momenten en gedragingen zichtbaar die anders niet opvallen in de snelheid van het stadsleven.”

Lagos

In Naarden zijn tijdens het Fotofestival 25 foto’s te zien die Losekoot maakte in Lagos, Nigeria. Deze stad behoort tot de grootste steden ter wereld, maar tegelijkertijd is er weinig over bekend. Het was lang de snelst groeiende stad van het Afrikaanse continent. In 2050 zou het wel eens de derde grootste stad van de wereld kunnen worden. “De bevolking is in Lagos niet heel erg gemengd met andere culturen Dat heeft verschillende oorzaken, bijvoorbeeld corruptie en het feit dat er weinig terecht is gekomen van politieke beloften. Het gevolg daarvan is dat mensen in Lagos veelal met oorspronkelijke leden van hun eigen stam bij elkaar wonen. De sociale codes worden door deze stammen bepaald. Iedereen kent elkaar, heeft een mening. Wanneer er iets gebeurd, dan bemoeit iedereen zich ermee. Dat maakte het voor mij lastig om daar te fotograferen. Dat kun je niet ongemerkt doen. Dus moest ik een andere methode verzinnen.”

Emotie

“Tegelijkertijd was Lagos de meest spectaculaire stad van mijn project om in te werken. Er gebeurt van alles. De stad is heel dynamisch. Emotie is alom aanwezig op straat. De vrouwen dragen tassen op hun hoofd en zijn gekleed in kleurrijke gewaden.” Een schril contrast met Londen. “Dat vond ik de meest afstandelijke stad. Ik heb daar een jaar gewoond tijdens mijn studie Photography and Urban Cultures aan Goldsmiths.”

Dorps

Ondanks zijn fascinatie voor wereldsteden heeft de fotograaf het in Amsterdam prima naar z’n zin. “Ook al is Amsterdam niet te groot en redelijk dorps, toch heeft het internationale allure. En het is klein genoeg om contact te maken met mensen op straat.”